Hello all, Saren here. I’m honored that Tetyana asked me to be her co-contributor to ScienceofEDs, and am looking forward to collaborating on the project. My interests and background tend more towards the clinical; I don’t have the neuroscience training that she does, so I hope to bring a slightly different perspective while remaining committed to the research focus of the site. I can be reached at saren[@]scienceofeds[.]org with any questions, critiques or suggestions – I’d love to hear from you!

For my first post, I’m going to focus on one of the basic areas that much of the recent ED research aims to address:

WHAT CAUSES EATING DISORDERS?

We hear a lot about how eating disorders are complex syndromes with multiple causes. Articles in the popular press run the gamut from asserting genetic risk factors to proclaiming that Facebook causes eating disorders. In addition, disordered eating practices and poor body image are often conflated with the full-blown clinical disorders, further serving to muddy the waters.

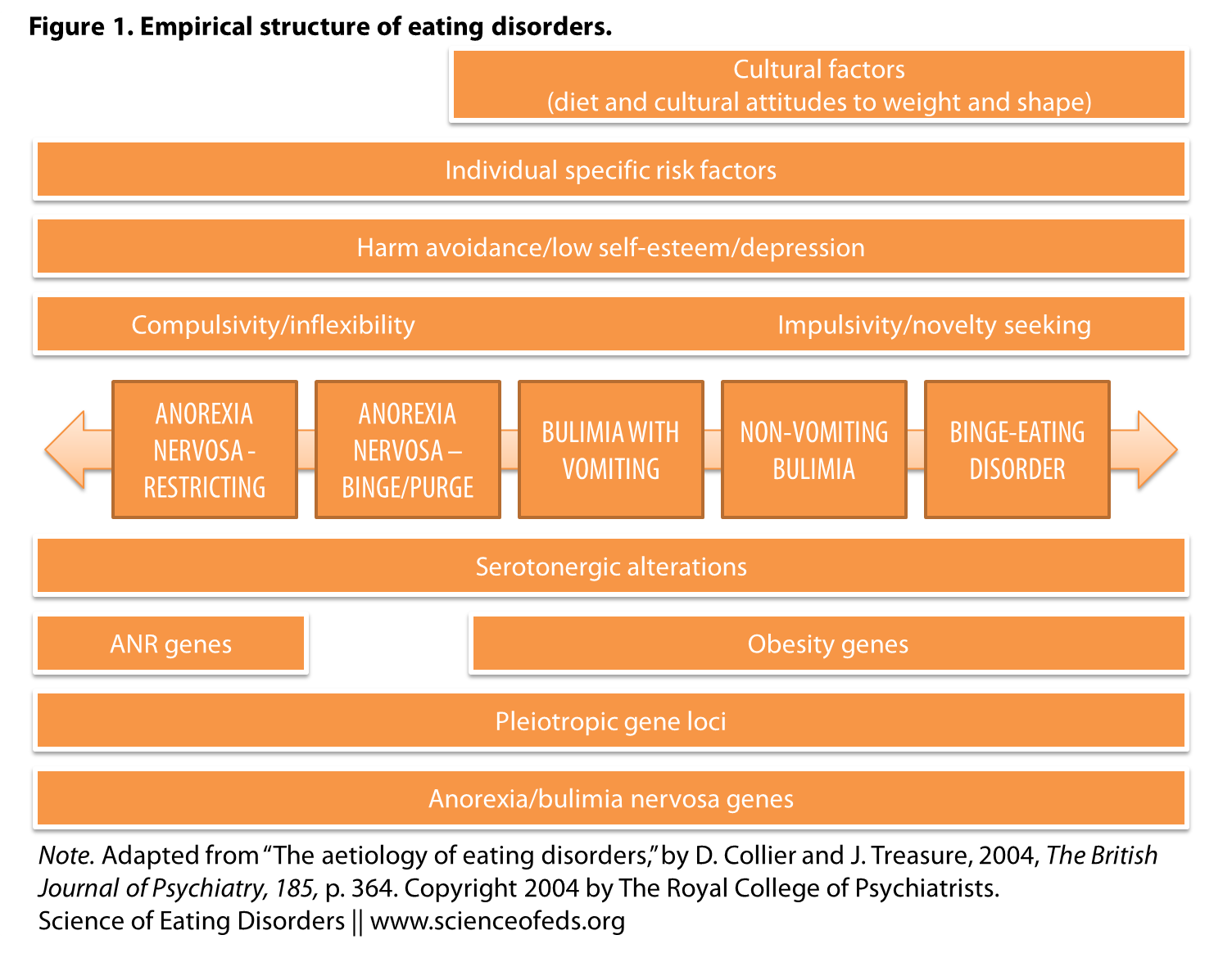

Eating disorders have long thought to be caused by familial conflict and sociocultural pressures regarding physical appearance, leading to a pathological drive for thinness and a desire to control eating behavior. However, particularly over the past decade, a body of research has emerged to complicate (and, in many cases, disprove) that simplistic and faulty explanation. Collier and Treasure’s 2004 editorial published in the British Journal of Psychiatry (“The aetiology of eating disorders”) provides a clear and concise overview of the various causative factors involved, and offers a graphic model of what the authors call “the empirical structure of eating disorders.”

What is “etiology”?

pronunciation: /ˌētēˈäləjē/

noun (plural etiologies)

- the cause, set of causes, or manner of causation of a disease or condition: a disease of unknown etiology; a group of distinct diseases with different etiologies

- the causation of diseases and disorders as a subject of investigation

…AND WHY DO WE CARE?

I wanted to give a quick overview of the Collier & Treasure model (which is, in general, the model of causation that’s currently accepted in the scientific community) in my first post.

- What we think “causes” eating disorders has significant impact on multiple overlapping arenas: It affects public perception of EDs (and therefore affects stigma/support for individuals, funding for research, access to treatment, and so on).

- It shapes the direction of research:

e.g., Much of the ongoing research regarding changes to the upcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual is focused on developing an empirically-based classification structure of eating disorders, as “our tendency to “study what we define” has created a gap between the problems that people have and what we know about those problems.” (Keel et al. 2012) - It influences treatment methods used, for both clinicians and patients (and this issue is particularly salient, in my opinion, because there are few evidence-based treatments for EDs, and those that do exist [Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, fluoxetine, Family-Based Therapy] have only demonstrated efficacy in certain subsets of the population).

SO, WHAt DO WE KNOW?

Collier and Treasure begin their review with a brief history of the ways that EDs have been conceptualized over the past century, many of which are still in use:

- pre-1970s: anorexia nervosa is seen as “a non-specific, environmentally responsive neurosis of women with its roots in the dysfunctional family.” (This view is still evident today – how many times have you heard that EDs are about “control”?)

- 1970s: anorexia is recognized as a discrete, specific disorder; bulimia nervosa is first described in 1979

- 1980s: binge eating disorder is first described; “eating disorders were thought of as an extreme manifestation of societal obsessions with thinness, with common subclinical syndromes present in the population.”

- 1990s: “causality shifted to gender dynamics, focusing on power and self-determination, rather than being related to the biology of female gender”; at the same time, preliminary evidence for heritability in EDs is found via family and twin studies.

- early 2000s: “sociocultural explanations include worldwide cultural dynamics, such as cultures in transition (‘Westernising’ societies) and confused gender identities”; there is an increased interest in exploring the biological and genetic components of EDs. ” At present, “however, little is known about this aetiology, particularly its biological components, and this is severely hampering the development of new treatments.”

The authors state:

Although there is no doubt that these sociocultural explanations are important and relevant, anorexia, bulimia and obesity are perhaps better regarded as heterogeneous disorders with complex multifactorial aetiology, involving the interaction of genes and the environment, particularly social factors.

This is their visual representation of that complex multifactorial etiology.

I really like this model, because it acknowledges the myriad factors that may be implicated in the development of an ED – and any of these factors may be present in an individual to a greater or lesser extent. I also like that it’s trans-diagnostic – it places the disorders on a continuum, with potential for movement along this continuum at different points in the individual’s lifetime. We’ve been talking a lot about diagnostic crossover here at SED, and it’s a discussion that is likely to continue, as it’s one of the issues that the DSM-5 work group on EDs is facing in their proposed revisions.

Pleiotropic trait loci: Pleiotropy occurs when a single gene effects multiple phenotypic traits, i.e. has influence on multiple areas in the body (can be on a cellular scale, as well). A hypothetical example of this would be (in super-basic terms) that the genes that may predispose someone to bulimia nervosa with self-induced vomiting may also influence traits like impulsivity and tendency towards obesity or higher natural body weight. Loci refers to the location of these genes on chromosomes.

I’m not clear why the top bar (“Cultural factors”) doesn’t extend all the way to the left to include anorexia nervosa. Also, the authors don’t appear to provide a rationale for differentiating anorexia – particularly the restricting subtype, noted above as RAN (AN-R in other studies and previous posts) – in this manner from the other forms of eating disorders beyond noting that in studies, RAN has tended to emerge as a distinct phenotype. Yet they also note that crossover between restricting and binge/purge subtypes is common, and I would have like to have seen more discussion on how they resolve these two phenomena.

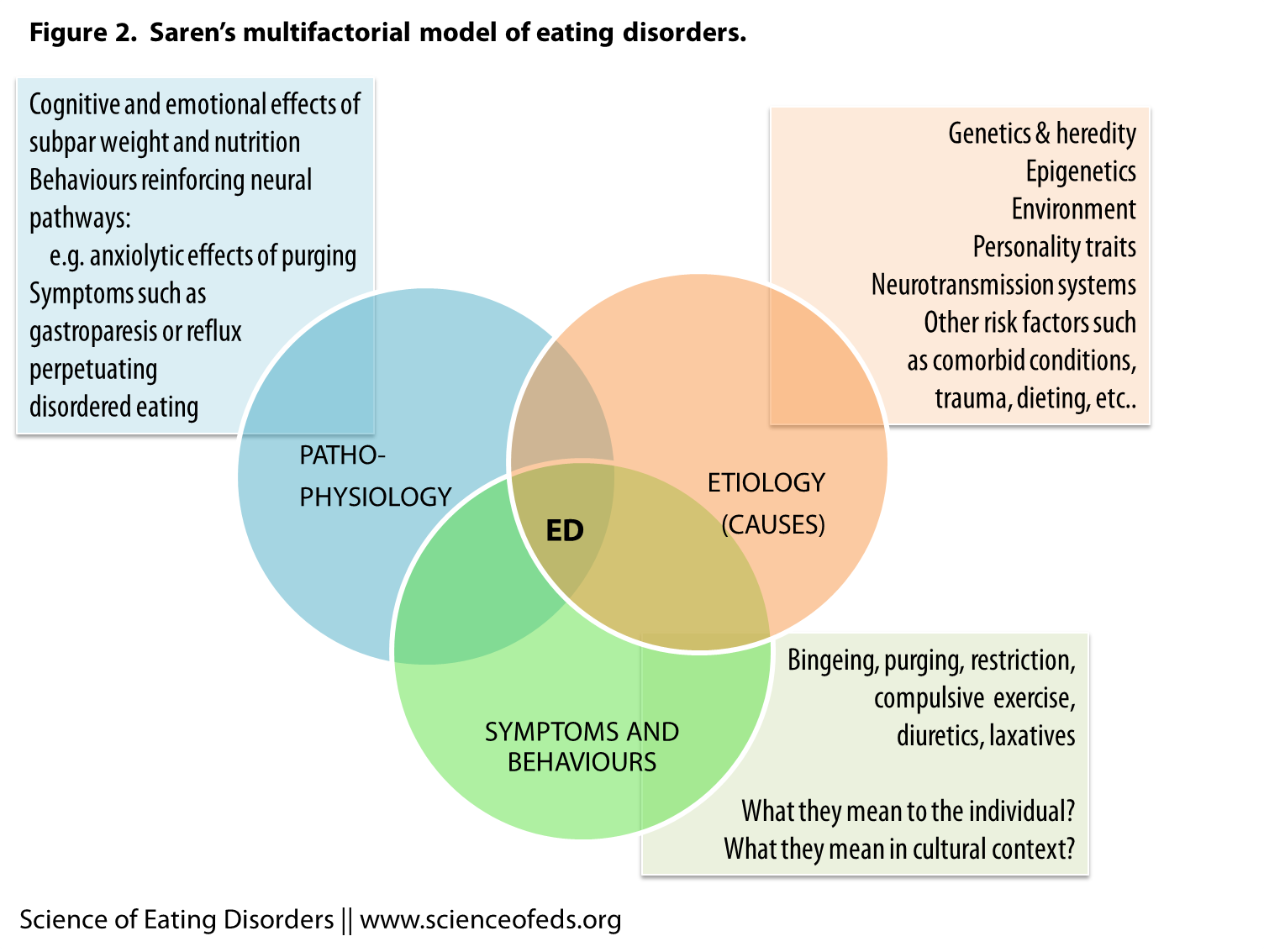

If I were to create a graphic model of eating disorders, it would look something like this:

Though obviously the above lacks the specificity of Collier and Treasure’s, not differentiating between diagnostic categories – and while theirs is focused on causal factors, mine can be read as both causal and perpetuating factors. Perhaps much of what we consider to be “cultural factors” in causing eating disorders are, more accurately, biological phenomena interpreted through a cultural lens? e.g., A behavior typical to anorexia nervosa is compulsive kinetic activity (or “exercise”). This is generally interpreted by the individual and those around him/her as an expression of fat phobia and desire to “burn calories.” Yet dietary restriction and weight loss has been shown to elicit hyperactivity in animal models in several studies:

For example, mice and rats given food for only 2 h per day and allowed access to a running wheel develop behavioural hyperactivity and weight loss analogous to anorexia nervosa. This points to fundamental mammalian behaviours that might explain some of the phenotypes seen in human eating disorders […]

The full text article is currently freely available in the online edition of the British Journal of Psychiatry, and I would encourage you to read it for discussion of the specific factors listed above; it’s written in an easily comprehensible style, is not overly technical, and fairly brief (2 pages.)

What do you think of the Collier & Treasure model? How does their “empirical structure” fit in with your conceptualization of eating disorders (on a personal or general level)?

References

Collier, D., & Treasure, J. (2004). The aetiology of eating disorders The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185 (5), 363-365 DOI: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.363

While I agree and appreciate their model’s recognition of the continuum between diagnoses, I am much more drawn to yours. I love that it addresses the perpetuity between symptoms, diagnoses, and causes. It really frames it in a “Chicken or the Egg” type manner, which often times is interlaced with other mental illness diagnoses; Was I bulimic because I was depressed? Or am I still depressed because I still have my eating disorder? Or are these both still present because of other reasons? (still in the same toxic causative situation/environment, genetics, etc…)

Great article 🙂 I look forward to more!