Anonymous asked, “I’ve never lost my period. Weight restored I am naturally thin, but even at a BMI of 15 or so I always got my period (although it wasn’t always regularly). This makes me feel like I’m not actually sick because I hear about everyone losing their period.”

eatruncats replied: “To the anon who asked about losing periods: For all the times she worries about not being sick enough because she never lost her period, there are people who lost their periods at BMIs of 18, 19, and 20 who worry about not being sick enough because they never got to a BMI of 15. If you have an eating disorder, you are “sick enough.” Period.“

As it stands now, amenorrhea–or the loss of three consecutive menstrual cycles–is a diagnostic criterion for anorexia nervosa. Individuals who have not lost their periods are diagnosed with eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). A problematic catch-all diagnosis that makes up the majority of those diagnosed with eating disorders. I’ve discussed some of the problems with the EDNOS diagnosis elsewhere, so today I want to focus on the problematic amenorrhea criterion.

Thankfully, in the attempt to make diagnostic criteria more scientific and evidence-based, the upcoming edition of the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) will not include the amenorrhea criterion. I say “thankfully” because there is mounting evidence that amenorrhea is not limited to any eating disorder subtype and that it does not reflect the severity of psychological or behavioural symptoms in eating disorder patients.

First, the amenorrhea criterion is inherently problematic because it can’t be applied to a lot people:

- males

- post-menopausal women

- women on hormone replacements (oral contraceptives/”the pill”)

- girls who have not yet reached puberty

- patients who haven’t been sick for a sufficient amount of time for menstruation to cease

The purpose of diagnostic criteria is to provide clinicians and healthcare providers with information about the nature of the disorder and aid in treatment decisions. From this, an argument could be made in favour of keeping the amenorrhea criterion if female patients who have lost their periods are significantly different from those who haven’t, and if this difference may differentially guide treatment decisions.

So are they?

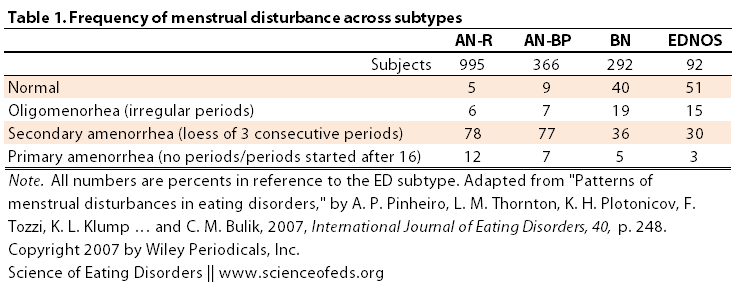

A study by Pinheiro et al (2007) aimed to examine “the differences in menstrual status across eating disorder subtypes” and “determine the association between clinical and nutritional variables, psychological, and personality features, Axis I and II comorbidity with menstrual dysfunction in women with AN, BN, and EDNOS.” The authors waived the amenorrhea criterion, for obvious reasons, and collected information from 1,705 women.

As you can see, a quarter of patients who would fall into the anorexia nervosa diagnosis did not fit the amenorrhea criterion. Conversely, roughly a third of patients with bulimia nervosa or EDNOS did.

These findings illustrate that individuals with variants of AN and BN present with amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, and normal menstrual function suggesting that menstrual status might not be an informative criterion to distinguish among ED subtypes.

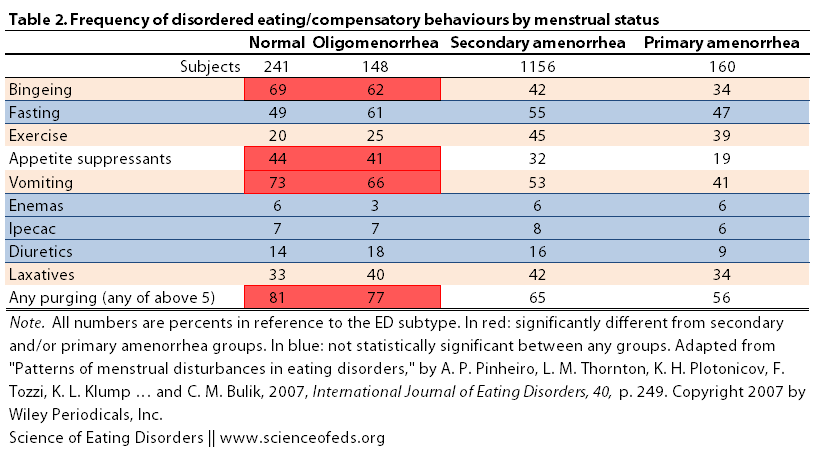

The next question the researchers asked was, will grouping the participants based on the menstrual status reveal any differences in the frequency of inappropriate compensatory behaviours or disordered eating behaviours? (Click to enlarge.)

So, there are no differences between the groups (normal menses, irregular menses, secondary and primary amenorrhea) for the frequency of fasting, and the use of ipecac, enemas and diuretics. I highlighted in red instances where groups with normal or irregular menses exhibited higher frequencies of certain behaviours. Specifically, the use of appetite suppressants, and the frequency of binging, as well as the frequency of vomiting were increased in the normal and irregular menses groups when compared to the secondary and primary amenorrhea groups. Moreover, these groups also differed in the frequency of using “any purging” method (from the five listed above).

The fact that the normal menses group exhibited increased frequency of bingeing and/or purging is not surprising, given that this group is composed of bulimia nervosa and EDNOS patients. But nonetheless, it is interesting to see, despite the differences, just how similar these groups are in many respects. There were also no significant differences observed for Axis I and II disorders across the four groups.

What about personality and psychological characteristics?

Pincheiro et al. found that:

- normal and oligomenorrhea (irregular) menses groups exhibited less “eating disorder rituals at the worst point of illness” than the secondary and primary amenorrhea groups

- oligomenorrhea and secondary amenorrhea groups scored higher on harm avoidance but lower scores on novelty seeking that the other two groups (This seems consistent with the personality differences generally observed between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa patients.)

- oligomenorrhea and secondary amenorrhea groups also scored higher on obsessions than the other two groups

Remember, statistically significant differences =/ every person fits the bill. No, it just means that taken together, there are observable differences between two groups, not that every person in that group scores higher/lower on a particular personality characteristic.

What about characteristics that didn’t differ between groups? These include:

- worst preoccupation and worst motivation to change

- trait anxiety

- compulsions

- concern over mistakes

- doubts over actions

- organization

- parental criticism and expectations

Long list, right?

All in all, these results seem to support previous studies, particularly those comparing anorexia nervosa patients with and without amenorrhea:

These observations are consistent with previous studies that used smaller samples… For example, Garfinkel et al. (1996) found no differences in psychiatric comorbidity (major depression, anxiety disorders, and alcohol dependence) when women with AN with and without amenorrhea were compared. Other authors reported similar depression scores and general psychopathology among females with typical and atypical AN (Cachelin & Maher, 1998; Watson & Andersen, 2003).

What’s interesting to note is that estrogen isn’t just involved in reproduction. It can also modulate all sorts of things, including our cognitive function and mood. So it may well be that some of the personality differences that these authors report between women who are and aren’t menstruating are not inherent differences between these two groups but the result of, at least in part, their menstrual status. In other words, the lack of menses might be contributing to the higher harm avoidance and lower novelty seeking seen in the amenorrhea groups might be due to their menstrual status. That gets us to the-chicken-or-the-egg question, or more appropriately, the-state-or-trait question.

But anyway, hormones can do a lot more than what a lot of give them credit for, which is definitely a topic I will explore in the future. (So much to blog about! So many things I want to discuss and write about! Exciting and overwhelming at the same time!)

As always, I like to point out the limitations of every study, which is important because we don’t want to extrapolate beyond what the data really shows.

- We can’t determine the cause-effect relationship in this study (loss of menses –> low novelty seeking or low novelty seeking –> loss of menses, or maybe they are completely unrelated)

- All the data was collected using self-reported questionnaires, meaning that it might not be as accurate as in the cases where patients are evaluated by clinicians

- Hormones were not measured

- Findings may not be representative of community or clinical samples because the participants were recruited for a genetic study

- Finally: it would’ve been nice to have a noneating disorder control group

The take home-message from this study is nicely summarized by the authors in their conclusion,

Women with ED, irrespective of menstrual status, experience similar degrees of psychological distress, and no distinguishing Axis I and II comorbid disorders. In summary, our findings suggest that varying levels of menstrual dysfunction are highly prevalent across all ED subtypes…

Taken together our results support reconsideration of amenorrhea as a diagnostic criterion for AN. Our recommendation is that the criterion be reconceptualized as an associated feature of AN, BN, and EDNOS with a broader indication of menstrual irregularity rather than amenorrhea of a specified and arbitrary duration.

References

Pinheiro AP, Thornton LM, Plotonicov KH, Tozzi F, Klump KL, Berrettini WH, Brandt H, Crawford S, Crow S, Fichter MM, Goldman D, Halmi KA, Johnson C, Kaplan AS, Keel P, LaVia M, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Strober M, Treasure J, Woodside DB, Von Holle A, Hamer R, Kaye WH, & Bulik CM (2007). Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40 (5), 424-34 PMID: 17497704

One Comment

Comments are closed.