I recently attended the International Society of Critical Health Psychology’s 8th Biennial Conference in Bradford, England. At the conference, I had the pleasure of attending many talks that challenged the way we approach health psychology. Luckily for me, there were several sessions that touched on issues of disordered eating and body image.

One such talk, a panel presentation with Hannah Frith, Sarah Riley, Martine Robson and Peter Branney, challenged attendees to re-think the way we approach body image. When I returned home, I immediately downloaded an article by Kate Gleeson and Hannah Frith (2006) that discusses this same idea and essentially begs the question: Is the concept of “body image,” as it is currently articulated, actually useful?

This might come off as a controversial question; after all, body image is central to many studies (and treatment programs) related to eating disorders. We’re told repeatedly that by improving our body image, we can achieve peace with food, with ourselves, with exercise, and with others. Good body image is upheld as the panacea of recovery and positive body relations.

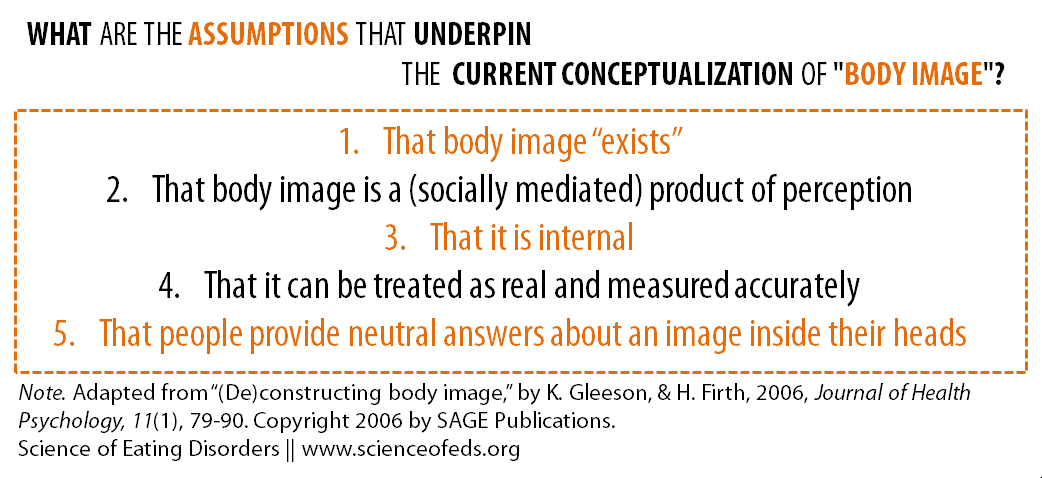

I want to make it clear that I think that the sentiment and intentions behind the “good body image” rhetoric is well intended, perhaps even admirable. However, I am intrigued by the way that Frith and others make explicit the assumptions that underpin current conceptualizations “body image” that may limit our understanding of how individuals relate to, act with, and on their bodies.

WHAT ARE THE ASSUMPTIONS THAT UNDERPIN THE CONCEPT OF “BODY IMAGE”?

1. ASSUMPTION: BODY IMAGE “EXISTS”

Hear me out; this isn’t actually as strange as it sounds. As body image is understood and studied, it is assumed to be a “thing” that all individuals possess and relate to. Whether or not this “image” is accurate, researchers assume that individuals have “it.” Otherwise, what use would measuring body image be?

Traditionally, body image was understood to be “the picture of our own body which we form in our mind, that is to say, the way in which the body appears to ourselves” (Schilder, 1950, p. 11). Rudd & Lennon (2000) expanded this definition to incorporate perceptions and attitudes held toward one’s body.

Much like other constructs, this assumption (i.e., the existence of body image) makes body image measurable, and would ideally enable us to explain why people engage in behaviours related to the body. For example, a researcher could hypothesize that an inaccurate body image could be behind a drive for thinness in anorexia nervosa, regardless of actual body size.

2. ASSUMPTION: BODY IMAGE IS A (SOCIALLY MEDIATED) PRODUCT OF PERCEPTION

Understanding that body image is a “thing” within the human mind leads us to believe that it is created through perception. Older eating disorder research in particular was enamoured with body image discrepancy. The authors cite Bruch’s (1962) and Slade & Russell’s (1973) research about the overestimation of body size in anorexia nervosa as examples of the way in which psychology has focused (perhaps unduly) on body image perception.

Despite this focus, studies are generally unable to find statistically significant associations between size estimation and body dissatisfaction. The perceptual focus also places an emphasis on the things that “distort” perception, such as cultural and psychological pressures. More recent research has focused on discrepancies in body image perception, for example, by asking women to choose which body among several examples would be their “ideal,” often finding that women choose bodies thinner than their own but not accounting for the “why” or for the impact that this has on thoughts, behaviours, and relationships.

3. ASSUMPTION: IT IS INTERNAL

Body image is generally articulated as something that “belongs” to individuals. Individuals, of course, exist in and are impacted by society. However, at the end of the day, these forces are seen as acting on individuals, changing their internal image of their body. Despite a barrage of research looking at the influence of socio-cultural factors on body image, we actually know relatively little about how exactly media images, for example, impact body image.

4. ASSUMPTION: IT CAN BE TREATED AS REAL AND MEASURED ACCURATELY

This assumption floats alongside assumption number one, and brings up a number of critiques about the ways in which body image is measured:

- Body image needs to be pared down in order to be measured: for example, studies asking participants to choose an ideal body out of a number of silhouettes may offer 9 different body shapes, which may or may not include the “ideal” body image held by participants

- Different responses are assumed to be representative of “real” perceptual differences

- These different responses are treated as inherently meaningful: any discrepancy is treated as dissatisfaction

5. ASSUMPTION: PEOPLE PROVIDE NEUTRAL ANSWERS ABOUT AN IMAGE INSIDE THEIR HEADS

Individuals are generally aware of their existence in a particular cultural milieu. While an individual might reply to a questionnaire stating that their ideal body image is thinner than their actual body, this says very little about where this falls on the individual’s priority list. They may just be re-articulating a societal imperative.

Individuals with and without eating disorders, for example, might respond to a body image questionnaire in this way, but not all individuals will engage in practices to bring about a smaller body size. There are many other factors that lead to behaviours (such as disordered eating) to “correct” body image discrepancies.

WHY DOES IT MATTER?

At this point, you might be shaking your head and wondering why bother making a case against something that has brought such attention to the sphere of body studies and disordered eating. Essentially, the authors acknowledge that such work has indeed led to a great deal of recognition for the reality of body issues. However, if we understand these issues, we can work toward a broadened, and hopefully more useful, conceptualization of body image that can help us to move forward with “body image” work.

RE-CONCEPTUALIZING PROBLEMS

1. Narrowed researcher focus

Body image is complex and diverse. By understanding it only as a mediator between thought and action, or something that drives behaviour, we forget to ask other important questions, such as:

- What is the experience of being in one’s body like for diverse individuals?

- How does one’s understanding of their body influence their everyday life and interactions?

- Are there other ways of understanding problematized behaviour (i.e., eating disorders, body dysmorphia)

2. Downplaying context

As previously mentioned, bodies exist in a socio-cultural context. Prior research on body image has located socio-cultural discourses and investigated the uni-directional influence of these discourses on individuals’ body image.

However, relatively little research has probed the ongoing and relational nature of body image, and how individuals interact with and negotiate these messages. People may experience their bodies differently depending on where they are, and who they are around, not just which messages they are exposed to.

3. De-emphasizing the discursive production of body image

When we treat body image as a “real thing,” we may forget to look at the social construction of body image itself and it’s cultural utility. I know that sounds a bit high-handed, but bear with me: there are many messages that use body image in instrumental ways to feed into various interests (i.e., big business, etc.); body image itself, and “ideal” body image is continually modified and re-articulated, rather than fixed and static.

4. Ignoring the social nature of perception

Perception of bodies, particularly our own bodies, may be evaluated in comparison to others, and also to ourselves. Rather than being a unified whole, body image may focus on particular body parts, for example.

Within a “body image schema,” individuals may privilege certain features, which are likely not the same for each person. The authors use the example of a woman who might accept larger hips, the authors suggest, if it meant that her breasts were also larger, if this is something she prefers in her own body.

5. Distraction from the dialogic nature of body image

The influence of media on body image is generally assumed (in health psychology, at least) to be uni-directional. This understanding significantly under-emphasizes individuals’ ability to be critical of the media messages that surround them.

The authors cite a study by Currie (1997; 1999), which discusses the ways in which young girls may both enjoy magazines and engage in comparison with the images within magazines while simultaneously critiquing the “thin ideal” represented in these cultural artifacts.

6. Individualization of body concerns

Once again, we’re brought face to face with the fact that we interact with others. We are not just acted upon, as passive bodies; we engage in interactions and think about what people are thinking about us.

Further, the ways in which people deal with body image discrepancies evidently differ from person to person. Not everyone consumes media messages in a uniform way, a fact that might be implicitly understood but remains relatively unexamined.

BODY IMAGING

So, with all of that said, how can we come to grips with body image, and make the construct more useful? The authors suggest, in line with Cash (2002), that body image might best be understood as an active, continually re-created, process. They prefer the use of the term “body imaging,” which captures the fluid and on-going nature of individuals’ body experiences.

To conceptualize body image in this way is to understand it as

an active process which the individual engages in to modify, ameliorate, and come to terms with their body in specific temporal and cultural locations.

Instead of being a “product,” body image can be understood as an “activity,” a distinction that the authors suggest may help to capture the complex and reflexive experience of being in one’s body.

I must say I was very intrigued by this re-articulation of body image. What I think is particularly interesting about this approach is that despite the rhetoric of “good body image,” we seem to be making little progress in actually improving the ways in which individuals relate to their bodies. This leads me to believe that we might be missing something in terms of our understanding about how individuals experience their bodies, and whether, indeed, “body image” is a concept that is universally and uniformly relevant to all.

References

Gleeson, K., & Frith, H. (2006). (De)constructing body image. Journal of Health Psychology, 11 (1), 79-90 PMID: 16314382

YES to all of this!

What stood out for me in particular (which is probably why I bolded it) was the point on how any discrepancy is viewed as a “dissatisfaction.” I don’t think I have a super accurate perception of my body, as I continue to be surprised at how “small” I am when I’m in a bathroom, say, with a bunch of full-length mirrors and other people around. So, my perception of my body is not entirely correct probably because I’m short and I don’t take that into account when I see my reflection, for example. That said, I have no issues with my body. I feel pretty sexy pretty much all the time, especially lately. I think I’m bigger than I am, but I still feel sexy and very comfortable in my physical body.

Anyway, there’s so much to say on this topic! Great post, thanks Andrea!

Thanks Tetyana, I really enjoyed writing it. I found myself nodding the entire time during their presentation- truly, it just makes a lot of sense to me. As you mention, perhaps one of the strongest points is the idea that discrepancy doesn’t necessarily equal dissatisfaction. Interestingly, my own perception can swing to either extreme, from perceiving myself as larger than I am to smaller than I truly am; but this is not always distressing, particularly as I am generally aware that neither is accurate. Another key for me is the recognition of the fluidity of “body image,” which makes it elusive in terms of measurement…

I first read Gleesen and Frith’s paper in 2007 when a Sociologist friend recommended it to me. I really like the paper and think the authors make some really pertinent observations. The construct of ‘body image’ is so vague and seemingly multifaceted. My understanding is that Gleesen and Frith prefer to use the term ‘physical appearance’ – which makes sense to me.

When people speak of ‘body image problems’ it’s actually quite meaningless because it’s not clear what they’re actually referring to: Body dissatisfaction? Misperception of body size/shape as seen in body dysmorphia?

Thanks for commenting, Cathy! You wrote: “When people speak of ‘body image problems’ it’s actually quite meaningless because it’s not clear what they’re actually referring to: Body dissatisfaction? Misperception of body size/shape as seen in body dysmorphia?”

Exactly. I think that “body image” is often used in conversation (and in research, for that matter) without really taking the time to delve into how the construct is being defined. Which not only makes it meaningless in terms of conceptual understanding, but difficult to compare between studies and come to any true understandings of what we’re really getting at.

Precisely. Thanks Andrea!

As Tetyana can witness (lol…) I have a Big Issue with the construct of ‘body image’ in the context of my own history of an eating disorder…. Basically, I do have body dissatisfaction, but I don’t see a cause-effect relationship between my body dissatisfaction and my history of eating disorder (anorexia nervosa = AN).

As you rightly state:

“….after all, body image is central to many studies (and treatment programs) related to eating disorders. We’re told repeatedly that by improving our body image, we can achieve peace with food, with ourselves, with exercise, and with others. Good body image is upheld as the panacea of recovery and positive body relations.”

I have found a big barrier to my treatment in the past is that therapists have focused very heavily on the way I feel about my physical appearance, with the assumption that if I am happy with the way that I look, then my AN will go away…. They have assumed that I have restricted food and over-exercised to the point of becoming and remaining very underweight because I actually ‘WANT’ to be very thin. (AN, unlike some other EDs can be very obvious to look at, and if a person is resistant to behaviour change, the assumption, quite plausibly, is that they must want to remain very thin).

In actuality, the reason why I have over-exercised and restricted food is that I have become TOTALLY STUCK in a pattern of very rigid and ritualistic, repetitive behaviours. I have felt that I HAVE to engage in those behaviours, in a very particular way. And if I break that behaviour pattern, my anxiety is utterly intolerable and I fall into deep depression. Thus, it is the behaviours themselves that have been the problem. I have become dependent upon the behaviours for the effect they have on my mood, NOT the effect they have on my physical appearance.

As for the way I see my body and the way I feel about it (i.e. ‘body image’), I actually perceive my body quite accurately. I see myself as too thin – which I am. I think the thinness is ugly. I see my nose as too large for my face – which it actually is, in part because my face is too thin! Big noses run in my family. That’s not a mis-perception; it’s a reality, and I don’t like the family nose!

I agree with this article and these comments, body image is such a broad topic, yet is the main reason why people are dubbed “anorexic” or “bulimic”. People have put such an important emphasis on physical appearance, and it has fogged our views when meeting a person and building relationships. This affects the perception we have for strangers, we form judgments and draw conclusions that are not necessarily true. In the US the social influence of the media portraying beautiful, thin men/woman, creates an idea or a norm that everyone needs to be like to be accepted. This article explains that body image is not measurable, people create a image in their own mind and because of their social environment, and culture they consider themselves, too skinny or too fat, which is untrue. Body image is a meaningless term that is used to often in daily conversations and it handicaps people from moving past the term and focusing on improving themselves for themselves and only themselves.