Achieving a healthy weight is a major goal of anorexia nervosa treatment. Indeed, a healthy weight is often seen as a prerequisite for psychological recovery. The fact that weight restoration is a crucial component of recovery is uncontroversial, the problem arises when it comes to determining what constitutes a healthy weight. How are ideal, optimal, or goal weights set? And who gets to decide?

Despite its recognized importance, there’s surprisingly little consensus on how target weight should be determined. Moreover, as Peter Roots and colleagues found out, when it comes to inpatient treatment centres in the UK and Europe, there is little consistency too.

In a study published in 2006, Roots et al. examined how treatment centres determine, monitor, and use target weight in the treatment of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. They also wanted to know the centres’ expected rate of weight gain, how often patients were weighed, who was involved in setting the target weight, and how target weights were used in the “therapeutic process and discharge planning.” They sent out questionnaires to 28 specialist inpatient ED services (17 in the UK and 11 in other European countries).

Twenty-one treatment centres responded. Non-UK respondents included centres in Denmark, Finland, Holland, France, Germany, Sweden, Spain, and Ireland.

I’ve summarized the main findings below.

How many treatment centres set target weights?

Out of the 21 centres, 18 set weight targets: 10 set target weights and 8 set target weight ranges.

How and when are the weight targets set (out of the 18 that set weight targets)?

Five set target weights prior to admission whereas nine did so on admission. Sixteen took into account age-related norms when setting the targets by looking at the weight:height ratio (9), BMI percentiles (5), and both (2).

Twelve set the targets according to service policy (what that means was not specified), four set them in negotiation with the patient (usually after a period of inpatient treatment), and two by considering individual variables such as parental and/or pre-ED weight. Interestingly, two services emphasized “the importance of not negotiating the target weight.”

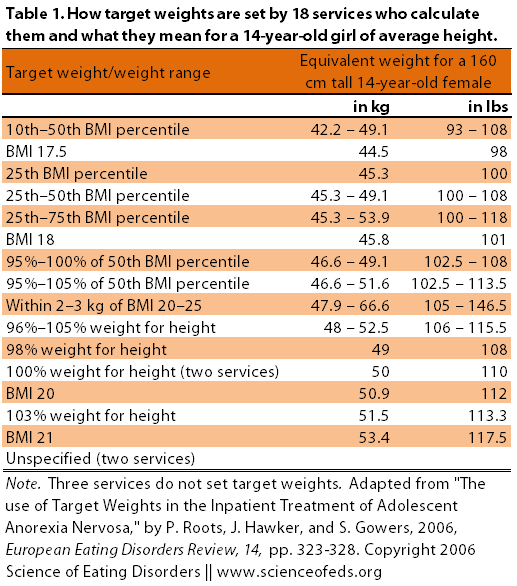

So, out of the 21 services there were fifteen different responses with regard to how target weights were set (see Table 1 below). Note that three did not set target weights and two did not provide information on how they calculate target weights, which means that out of 16 responses, only two were the same.

What is the expected rate of weight gain?

Services ranged from 0.3 – 1 kg per week (~0.6 – 2.2 lbs) per week; most expected a consistent rate of weight gain throughout (~0.8 kg or 2 lbs per week).

The table below details the different ways that various services set their target weights and what those targets “mean” for a 14-year-old, 160 cm tall female (that’s around 5’3″).

Interestingly, a third of the services (7) used pelvic ultrasound scans to “inform progress” and some of the services used the information gained to alter, if necessary, the target weight. I thought that was interesting because I wouldn’t have predicted it to be so popular. Indeed, I had never heard of using pelvic ultrasounds to inform target weight until I was researching around before writing this post and came across this post: Using Ultrasound to Predict Weight Regain in Anorexia Nervosa and Carrie’s post here.

Weight Gain and Discharge

Given that weight gain is an important component of treatment, it is not surprising that it is also an important factor influencing discharge. Out of the 21 centres:

- In nine places, discharge depended on reaching the target goal/goal range, and seven required a period of weight maintenance (ranging from 1 – 6 weeks)

- Eight, in addition to weight, also relied on “parental confidence” and “patients taking responsibility for food intake” when deciding on the appropriate discharge time

- Two mentioned including “emotional or psychological change” as being important factors in determining discharge, with one of these reporting moving away from using target weights and focusing on issues of emotional regulation instead

WHAT DOES ALL OF THIS MEAN?

For one, the lack of consistency among ED services in determining the target goal weight, expected rate of weight gain, and discharge criteria means that a 14-year-old girl weighing 36 kg on admission can be discharged at:

- a BMI of 16.5 after 13 weeks of treatment in one centre (~0.5 kg/week),

- a BMI of 18 after 10 weeks of treatment in another centre (~1 kg/week),

- a BMI of 18 after 33 weeks of treatment in a third centre (~0.3 kg/week),

- and a BMI of 21 after 20 weeks of treatment in the fourth centre (~1 kg/week)

As Roots et al. point out, the target weight for this patient can vary by over 11 kg (that’s over 24 lbs) and the total length of admission can vary by 23 weeks — and that’s just among the treatment services evaluated in this study.

In a study of Australian dietitians, Rocks et al. (2013) found similar variability in how target goal weight was determined:

Twelve dietitians reported that weight targets were commonly set for inpatients in their facility and this was usually determined by the multidisciplinary medical team. The remainder of practitioners stated that weight targets were based solely on the needs of an individual patient. The target weights were defined using: target weight (10 dietitians), target body mass index (8), or target weight range (9) or target BMI range (8). The specifics of weight targets were commonly dependent on individual characteristics, for example, normal weight for height percentiles, developmental stage of inpatients, and the treatment plan and management policies of the treatment facility. However, a minimum of the 10th and 15th BMI percentiles, the 50th BMI percentile, and an adult BMI of 20 or 21–25 (a healthy weight range) were also quoted as targets used in practice.

MY THOUGHTS…

Target goal weight is a funny thing. On the one hand, recovery means moving away from focusing on weight but on the other hand weight restoration is important (and many would argue necessary) for psychological recovery. Moreover, treatment services have to have discharge criteria — after all, we don’t have unlimited resources and we do want to offer treatment to as many individuals as possible (I think, anyway). New patients have to be admitted and others have to be discharged eventually.

Besides, as I’ve written before, inpatient treatment has its own drawbacks, so sticking around too long in an IP or residential setting may not be a good idea either. (It depends on a lot of factors of course.) That said, a low BMI at discharge is associated with relapse and poor long-term outcome (here, here, here, here, and here; some of these show that a higher BMI at discharge is predictive of a favourable outcome).

Finally, although weight restoration and resumption of menses are important, the focus on achieving a goal weight can become counter productive not only because it can make patients feel like the only thing that clinicians care about is their physical recovery (and not psychological state) but also because patients themselves can become obsessed with maintaining that goal weight (and not a pound more). That, I think, is still quite disordered, particularly considering how arbitrary these goal weights can be and how wrong clinicians can be about what they consider a “healthy” weight (see example here and here). (Though, to be fair, it is probably less physically damaging, which is not nothing.)

BMI values provide a quick and easy way to assess physical recovery. I think all of us — patients, caregivers, and clinicians alike — want to believe that a healthy weight = a healthy state. We all know it is not true, but we want to believe it is. Achieving that healthy state usually takes a lot (sometimes a loooooooooot) longer than achieving a healthy weight, and arguably , a lot of that progress must be made outside of the hospital (or residential treatment) walls.

Still, discharging patients when they are only at their target weight because they’ve been practically forced to gain (and are already making plans to lose it), when they haven’t yet reached a healthy weight, or when they are told that a certain weight is healthy when it isn’t healthy for them is not a good foundation for recovery post-inpatient (to say the least).

Roots et al. pick up on this:

As reported previously (Gowers et al., 2002), psychological factors are much less important for monitoring progress and deciding on discharge. This is surprising given the psychological basis of the condition and the well-documented frequency with which patients restrict their dietary intake as soon as they are discharged.

It is a bind, really. Achieving a healthy weight is important but determining what is a healthy weight (especially for a growing adolescent) is hard. Achieving a healthy weight is important for psychological recovery but focusing too much on a weight goal (especially an arbitrarily determined weight goal) is counter productive for recovery because it can fuel disordered thoughts and take time away from focusing on psychological recovery.

But goals are important and weight is an easily quantifiable goal. Besides, I’m not sure how well I would’ve taken to the concept of just letting my weight stabilize at whatever point is healthy for it… to “just eat” — and I wanted recovery and fought for it. But it was still scary. Trusting my body is a concept I am still getting used to — even after maintaining the same weight and eating really well for quite a while.

Roots et al. conclude with the following:

Whatever the theoretical issues about setting an ideal weight, inpatient services may be choosing to make unilateral decisions on target weight setting based on population norms rather than taking an individualised approach because they feel this is more therapeutic. Giving patients a clear non-negotiable, relatively easily quantified goal to work towards may allow them to better concentrate on their treatment. However we should be aware that targets set may not necessarily be valid markers of recovery. The wide variation in target weight setting, the implications for length of hospital admission and therefore cost, highlighted in this study may give cause for reflection on the validity of the choice of in-patient targets weights

I don’t think there’s a perfect solution for these dilemmas, but I do think it is important to think about them anyway.

References

Roots, P., Hawker, J., & Gowers, S. (2006). The use of Target Weights in the Inpatient Treatment of Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa European Eating Disorders Review, 14, 323-328 DOI: 10.1002/erv.723

Size of skeletal frame is a factor too, I think. My skeleton is slim in width, and I wish it were wider so that I could look a bit chunkier, yet not *feel* flabby.

I think that if a goal weight is set, it should be low. The lower it is, the more ED patients are going to accept it. I am officially ‘underweight,’ but whenever I’ve had full health checks (bone density, blood pressure, etc), I’m always healthily above average in every respect.

“I think that if a goal weight is set, it should be low. The lower it is, the more ED patients are going to accept it.”

Sure you can set a low weight, but then: what is “low”? setting a low weight with respect to the actual healthy weight for that person, even though it may actually be in the so-called “healthy” range, or setting a weight that most people consider to be low, like a BMI of 18.5 or something?

The problem with setting a low weight is not only is that, statistically, a big predictor of relapse post-treatment, it also defeats the purpose of treatment and recovery. The point of treatment is, hopefully, more than just to restore someone’s weight so that they are out of the medical danger zone. The problem with treatment is exactly that: Due to incompetence and limited resources, that IS what ends up happening. That’s not treatment though. Or well, it is crappy treatment.

No, the goal weight range should be (1) only ONE of many components of the overall treatment goals and (2) should be based on much more than just BMI values or pre-ED weight (especially for adolescents!). And the range should be something that’s reasonably healthy fora that individual based on growth charts/percentiles, parental weight, physiological signs, etc.

Setting a low weight is something that I’d agree with when it comes to treating chronic and severe AN. That’s the harm-reduction approach, and it is sometimes the only option (particularly if treatment has failed the person time and time again). It should never be the first option, though. We know, based on research, that it is not a good idea. The purpose of that research is to, hopefully, inform practice, right. One would hope.

Natasha, my response to your comment is much more anecdotal/soft-sciencey than Tetyana’s. I hope that’s alright.

My experience is that people with eating disorders often have irrational fears that can’t be fixed with “rational” fixes.

The following is an imperfect analogy, but one that helps me:

Imagine I was deathly afraid of spiders, and had to sit in a room with 15 spiders every day to cure me of some awful disease. I spend weeks delaying treatment and complaining to my doctor about the number of spiders, because I’m terrified!

My doctor tries to compromise with me: “Well, if you’re that scared I guess you only have to sit with 12 spiders”.

Here are the thoughts that are going through my head: “If 12 will work, he must have been lying to me about needing 15 spiders…this doctor just wants to make me a spider-lover! Maybe he’s lying about needing 12, too…This guy doesn’t know what he’s talking about!…I’ll see if I can talk him down to 9. Or maybe they can just put the spiders in the next room…Why does he want me to have fewer spiders when he knows I need them? Maybe I don’t need them at all! They must really be dangerous!”

My doctor was trying to make me more comfortable, but now I’m freaking out about whether or not I even trust him! And I’m not any closer to getting in that room.

What I really need is for the doctor to say “I know this is hard, but this treatment is exactly what you need, and I want you to know that it’s perfectly, completely safe. We just need to focus on getting you through that door and into the room. It’s okay to be scared; you can still do it!”

It might make sense at first glance to set a patient’s target weight low so that she will “accept it”. But when my nutritionist did this to/for me, all it did was

(1) make me think that I really WAS in danger of getting fat and that my nutritionist was so worried about me being fat she was trying to protect me from it,

(2) give me a lower number to launch new negotiations from, and

(3) make me think I could be recovered at a weight I couldn’t maintain without restricting.

Yes, some people may recover at weights that are technically “underweight”. No, this is not common (see studies cited in this article), and it also doesn’t justify the practice of setting target weights too low.

As they say to clinicians in FBT modalities, “don’t be afraid of what the ED is afraid of”!

Great analogy, Lauren, thanks. I get that you’re right in most cases.

But in my own case, I’m told that my healthy weight range is between 8 and 10 stone (112 pounds and 140 pounds). I have a small frame (tiny wrists, for example). I weigh a few pounds less than 8 stone, which is where I’m happy.

If I were told in treatment that I MUST reach 8 stone and stay there, I would totally go for it in order to get well. If I were told that I MUST reach 10 stone and stay there, I 100% would not. I would reject treatment.

A natural low BMI is the exception, not the rule. The goal of treatment for adolescents should be recovery from an eating disorder, not maintenance of a sub-threshold ED because it satisfied their disordered eating state.

I also think your point could’ve been just as effectively made without the use of specific numbers.

I just wanted to say thank you for this article! Although this is my first time commenting here, I read often. This article really struck a cord with me, though. I just wanted to pipe in that, as someone who has struggled with anorexia for a long time and is now an adult, I do think the setting of accurate weight goals even for those of us who have suffered for a long time and as adults is important. When you are truly in the anorexia, you’re not going to be more likely to agree to treatment just because someone tells you it will be ok to stay at a BMI of 18.5. You either agree to treatment or you don’t. You submit to treatment when you know that you want to live and confront the fact that you can not live the life you imagine for yourself while starving yourself. Although, seeing us suffer with the fear of gaining and food, treatment providers may want to soothe us by saying we can stay thin (and, btw, to an anorexic a BMI of 18.5 sounds just as scary as 20). Although in the instant this may soothe anxiety, it ultimately does us a disservice.

Things were a bit different to me. While my last dietitian was by no means okay with a BMI of 18.5 for me, part of what kept me in treatment with her was the fact that her meal plan and target weight range felt more manageable and realistic than previous treatment providers. While it was still scary, the lower target felt more tolerable – and proved to be more sustainable – than previous, higher targets; it *did* help me agree to treatment.

I was honestly very surprised that so few treatment centers actually take into account an individuals weight history, family weight patterns, etc. Given how ubiquitous the message to trust one’s body is in e.d. recovery, you would think that treatment providers would want to model that, rather than setting a universal standard and expecting patients’ bodies to fit that. I’m also shocked that so few places work with target weights instead of target ranges. One of the things that people all seem to be told at some point in treatment is that it’s natural for weight to fluctuate a bit, even throughout the day. Yet, a single target number instead of a target weight *range* goes directly against that. I went to a treatment center where the dietitian set individualized weight ranges (with a minimum of five lbs and a maximum of 10lbs) based on patients weight history, e.d. history/status, physical build/frame size, family history, and medical status. While we would know our ranges, all we would be told by the dietitian was if we were in range or out of range. Even our meal plans had ranges; for example, instead of getting, say, 9 protein exchanges a day, we would be told we need 9-11. It was very effective in not being able to focus on getting the “perfect” number in terms of either weight or meal plan. Having a specific target number that is not flexible can reinforce the overblown value that e.d. patients already place on weight.

Interesting that we had such different experiences. Why was your dietician willing to set a low goal weight of 18.5 while she wasn’t ok with it? That doesn’t seem to add up, but if it worked for you and got you to agree to treatment, that’s all that matters I guess. Why do you think that you were more willing to agree to treatment, based on a lower target weight? When I was in the depths of my eating disorder, a normal/low target weight was just as scary as anything else, so it didn’t really matter. I think when I was starting treatment, I didn’t really think that much about target weight that much actually…

But, I do know that having been given relatively low target weights (eg-“first we want to get you to X) has had a negative impact in the long-run, as now I feel like I should stay at this low-but-healthy weight, despite the fact that it’s not really where my body wants to be…

I should clarify. She did not set a target of 18.5 for me. (She also wouldn’t set one number like that.) My target range was well above 18.5, but lower than had been encouraged for me in the past. While I anticipate that at some point in my recovery I might choose to eat more intuitively and see where my body settles, having that initial target that felt more reasonable than previous ones made me more willing to try.