How many calories do patients with anorexia nervosa need to eat to gain a kilo (2.2 lbs)? It seems like a simple question and one that we should have figured out a long time ago, given the importance (err, necessity) of refeeding and weight restoration in recovery from anorexia nervosa.

Unfortunately, research in this area has often led to contradictory results (see Salisbury et al., 1995 and de Zwaan et al., 2002 for reviews). Fortunately, a paper by Stephan Zipfel and colleagues (2013, freely available here) sheds light on one potential cause of the discrepancies.

But first, some definitions:

TDEE stands for total daily energy expenditure. TDEE has three components: resting energy expenditure (REE), dietary-induced thermogenesis (DIT), and activity-induced thermogenesis (AIT). The gold standard for measuring TDEE is through something called the doubly labelled water technique. REE is usually measured through indirect calorimetry. (These techniques were used in this study as well.)

Generally, when people lose weight, their REE is also reduced as a result of decreased body weight and decreased lean mass, as well as metabolic adaptations. Since REE contributes significantly to the total energy needs, we’d expect it to also decrease in AN patients. However, previous studies on this are contradictory; some have found decreased TDEE to be decreased in AN patients whereas others have found it to be similar to healthy controls (see de Zwaan et al., 2002).

Unsurprisingly, the amount of excess calories (calories in addition to those calculated to be required for basic survival) needed to gain a kilo (2.2lbs) have also varied widely between studies: between 5340 and 9768 (Forbes et al., 1984; Dempsey et al., 1984, respectively).

Part of the discrepancy might have arisen from the use of different techniques to measure basal calorie requirements, but even in studies using the same technique (indirect calorimetry), the excess calories necessary to gain a kilo differed by more than 2,000 (Russell and Mezey (1962) versus Dempsey et al. (1984)).

Clearly, some else must be going on. As Zipfel et al. point out, previous studies did NOT distinguish between patients with high- and low-activity levels. It is possible that the discrepancies in energy requirements and excess calories required to gain a kilo arise, at least in part, from this.

THE STUDY

To assess the effect of exercise on energy metabolism, the researchers recruited 12 AN patients (all females, average age ~22 years, average duration of illness ~4.5 years) and 12 healthy controls. All AN patients had amenorrhea; 8 had AN restrictive subtype and 4 had AN binge-purge subtype.

There were no differences in the amount of daily exercise between the AN and control groups. However, differences emerged when the researchers divided the groups into high- and low-level exercisers. Seven of the AN participants were categorized as “high-level exercisers” compared to only two in the control group. (All the binge/purge AN patients were in the high exercise group.)

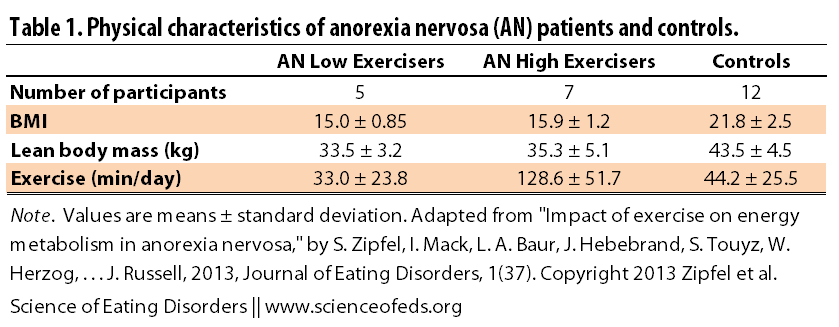

The table below illustrates the breakdown for BMI, lean body mass (body mass – fat mass), and duration of exercise per day.

As you can see, the high-level group exercised 3-4x more than the low-level exercisers and the controls. They had slightly higher BMI and lean body mass values but these were not significantly different from the low-level exercisers.

THE MAIN FINDINGS

Here’s where the interesting part comes in. When Zipfel et al. compared REE between the AN group and the controls, there was a significant difference — as you’d expect given that, for one, there are significant differences in BMI between the AN and control groups.

However, when the REE was adjusted for body surface area or lean body mass, those differences disappeared. What that means it that, taken as a group, a kilogram of lean body mass (lean body tissue is much more metabolically active than fat tissue), AN and controls in AN patients was as metabolically active as in the controls. It had the same energy needs.

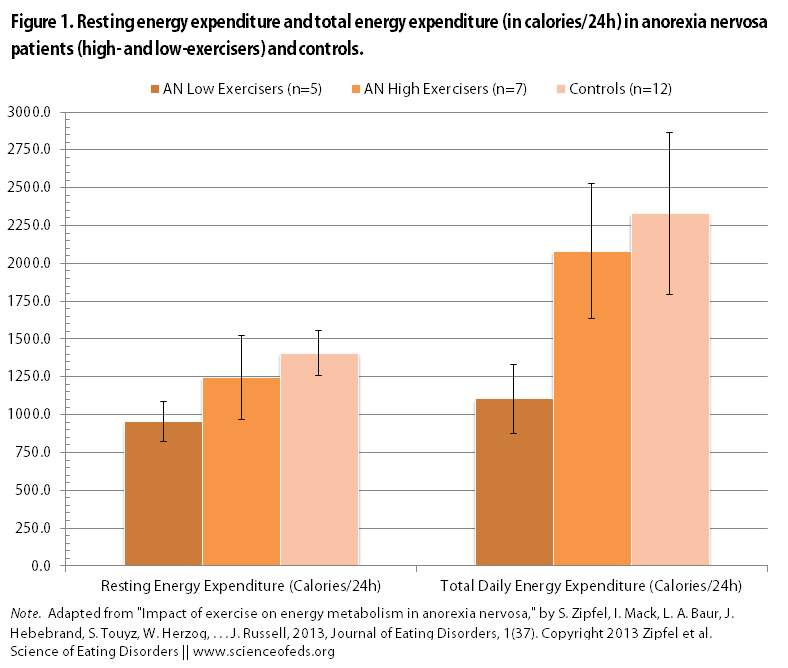

Then the researchers split up the AN group into high- and low-exercisers and did the comparisons again. I’ve illustrated the main findings in the two figures.

The main finding: Resting energy expenditure in high-level AN exercisers was NOT significantly different from healthy controls. This means that AT REST, high-level AN exercisers require, on average, the same amount of calories as normal-weight healthy controls. This is despite the fact that there were significant differences in lean body mass, leptin levels, and T3 levels.

Unsurprisingly, REE in the high-level AN exercisers and the healthy controls were significantly higher than in the low-level AN exercisers group.

There were also NO differences in the TOTAL energy expenditure between high-level AN exercisers and healthy controls, but both expended nearly twice the amount that low-level AN exercisers did.

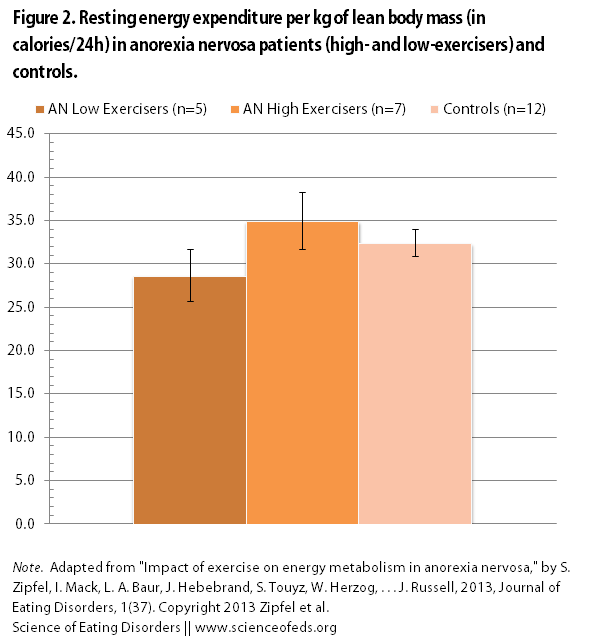

When the researchers adjusted the REE for lean body mass, they found that high-level AN exercisers actually had higher resting energy expenditure per kilogram of lean body mass (see Figure 2 below).

This makes sense because the similar overall REE levels have to be driven by something and we know that both high- and low-level AN exercisers have significantly less lean body mass tissue than the healthy controls. (Of course, it is not just lean body mass that could be causing the high REE, but as I said, it is a significant factor, so it is not surprising.)

While the researchers don’t know what’s causing the differences in the REE between high-level and low-level AN exercisers, they do hint at where we may want to start looking for them,

No differences in thyroid hormone levels were observed between the AN subgroups. In fact, two individuals of the same LBM can differ considerably in their REE due to differences in heredity and a range of physiological factors [34]. The elevated REE in high-level AN patients is possibly caused by a secondary effect resulting from the impact of physical activity on a range of physiological processes that in turn influence REE [34,35]. Additionally it is also conceivable that the body core temperatures within the AN subgroups are slightly different [9]

Zipfel et al. also found that high-level AN exercisers had significantly higher driven for thinness and depression scores compared to the low-level AN exercisers. It will be interesting to see if this holds up in a larger study as there was quite a bit of variability in the scores, especially for the depression questionnaire.

LIMITATIONS

One of the obvious limitations is the small size, although I don’t actually think this is a big problem in this study given the stark differences in the variables of interest. A higher number of participants would likely decrease the variability within the groups but I am not sure it would change any of the relationships (i.e., similarities and differences) as far as the REE and TDEE are concerned. Larger studies are needed, however, to better understand what’s happening on a biological (and psychological) level.

The other limitation that the authors point out is that, outside of a structured interview, they did not assess the types of activities that the participants engaged in. Thus, they were not able to differentiate between, for example, short bouts of intense exercise or near-constant fidgeting, for example. This would be interesting to assess in future studies.

CONCLUSION & CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Taken together, our study shows that there are marked differences in energy requirement among AN patients. Over one-half of our AN patients reported high exercise levels directly related to weight control with an overrepresentation of the binge/purge AN subgroup.

I think one of the most clinically relevant findings of this study was that the researchers found that the question “What percentage of your exercise is aimed at controlling your weight?” was able to utilized to distinguish between low-level and high-level exercisers and thus significantly correlated with total energy expenditure when the cutoff was set at <50%.

I think this is pretty neat because, if its predictive value holds up in larger studies, clinicians can use a single question to better assess the energy requirements of their patients and thus better predict the calories required for weight gain. Asked directly, the patients may under-report, so an indirect question, like the one above, would be ideal to “solve this problem” (as the authors put it).

(Please note that I used “calories” throughout the post and in the figures for simplicity’s sake/because of its common usage but, strictly speaking, I’m really referring to kilocalories.)

References

Zipfel, S., Mack, I., Baur, L.A., Hebebrand, J., Touyz, S., Herzog, W., Abraham, S., Davies, P.S., & Russell, J. (2013). Impact of exercise on energy metabolism in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 1 (1) PMID: 24499685

This is interesting. What I’m not clear on, however, is whether or not they were still actively engaged in the physical activities. The paper indicated the study started after a two week stabilization period, but I”m not clear as to whether or not they were also permitted to maintain their same activity level during that time. I would assume if their activities were restricted even just for two weeks that it would have some impact on their REE and TDEE.

This is a very, very good point! I’ll the corresponding author about this.

Awesome. Thanks!!!

You know what, thinking about this more, they couldn’t have been given the way that TDEE was measured. It was measured over 15 days with the doubly labelled water technique, meaning that they must’ve been able to retain their typical exercise routines.

I do wish there was more information about the methods with respect to average daily calorie consumption over that time, whether their weight had changed in those 15 days (I’d assume that could influence things?), and I would be interested to see the relationship between REE and TDEE for each person (on like a scatter plot or something).

I wish I knew more about this topic — I have a lot to read. It is not something that I’ve learned much about (or was ever that interested in, metabolism), but given how often I’m asked various questions surrounding “how many calories should I eat,” I thought I’d blog about it to the best of my ability. I think the differences in TDEE between AN patients (almost 1,000 calories!) is pretty remarkable and I do wonder what’s “behind” the increased energy requirements of the lean body mass tissue. (Must. Read. More.)

Ahh. Good point. I agree that I wish there was more information about he specifics of their diets etc. There are so many factors involved that can make a difference so it’s hard to figure it all out. I’ve become more interested in metabolism issues as well, so I hope you continue to keep us updated on what else you find! Thanks so much for all that you do already! You are a huge help in sorting through this information!

Is the higher sd value for lean body mass for the high-exercise AN group likely to be an expression of differences in type of exercise (primarily aerobic Vs strength-based)? If so, it would be interesting to see a study where high-exercisers are divided into low Vs high lbm (by explicitly seeking Ps whose exercise is mainly strength-based?) as presumably the latter group would have an even higher REE. Differences in lbm could easily be genetic, but a question about exercise type would also be easy to screen with.

Also, I might be reading this incorrectly, but I think you’ve got the numbers in each of the subtype groups the wrong way round, otherwise not all the AN-BP Ps could be included in the high-exercise group.

Good catch regarding the numbers! It was a mistake on my part: 4 had b/p subtype (not 8) and 8 had restrictive subtype (not 4). I added that sentence after I published the post (which always seems to increase the likelihood that I mess something up).

You raise a very, very good point regarding the higher standard deviation value for the high-exercise AN group. I think that would definitely be a good thing to look into next, though they’d definitely need a higher number of participants to parse that out. I think it is not only that (aerobic vs. strength-based) but also intensity of aerobic exercise AND duration of exercise. The authors mention that as a limitation of their analysis (they didn’t look into the kinds/type of exercise people did, and whether they were doing 30 mins of intense cardio or pacing around all day for example). It is definitely hard to say at this point because they didn’t look into it and the participant numbers are small. I wonder if those focused more on strength-based exercise would have higher REE. I don’t know enough about this stuff — certainly more LBM = higher REE but it is also my understanding that one’s metabolism is increased post-exercise too? (Seriously, I know very little about exercise physiology).

What I like about this study is that it has the potential to at least partly explain all the contradictory (or at least, highly variable) findings in previous studies looking at how many excess calories are required to gain a kilo, for example. I wouldn’t have expected that high-exercisers’ total daily energy expenditure is nearly double that of the low exercisers.