Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, is a common childhood disorder. ADHD can often persist into adolescence and adulthood. The prevalence of ADHD is thought to be between 6-7% among children and adolescents and ~5% among adults (Willcutt, 2012).

Increasingly, evidence from multiple studies has pointed to comorbidity between ADHD and eating disorders (EDs). For example, one study found that young females with ADHD were 5.6 times more likely to develop clinical (i.e., diagnosable according to DSM-5) or subthreshold (i.e., sub-clinical) bulimia nervosa (BN) (Biederman et al., 2007). Another study found that found that 21% of female inpatients at an ED unit had six or more ADHD symptoms (Yates et al., 2009).

However, most previous studies are limited by the fact that they assessed comorbidity between ADHD and EDs among patients. This limits our ability to generalize these findings to community samples, where many may experience symptoms of the disorders at subthreshold levels. Moreover, most studies focused on bingeing/purging behaviours and did not investigate differences between ADHD subtypes.

In the current study, Jennifer Bleck and colleagues sought to expand upon a previous study (published in 2013) and address the following questions:

- Do clinical/subclinical ADHD and clinical/subclinical EDs co-occur in a nationally representative sample?

- Does the relationship differ by type of disordered eating behavior and or ADHD subtype?

Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Bleck et al. analysed data from 12,262 participants (51% females). EDs were assessed when participants ranged from 18 to 27 years (average age was 21.8 years). The majority of participants were Caucasian (67%), 15% were African-American, 11% were Hispanic, and 4% were Asian.

SUMMARY OF MAIN RESULTS

Clinical Disorders

- 5.5% reported having been told by a health care provider that they had ADHD

- 2.1% reported having been told that they have an ED

Subthreshold Disorders

Among those who were not told they had an ED or ADHD (i.e., excluding the above 827 participants):

ADHD:

- 3.9% reported inattentive ADHD behaviours

- 8.5% reported hyperactive/impulsive ADHD behaviours

Eating Disorders:

- 7.1% reported bingeing and/or purging behaviours

- 14.3% reported restricting behaviours

WHAT ABOUT COMORBIDITY BETWEEN ADHD and EDs?

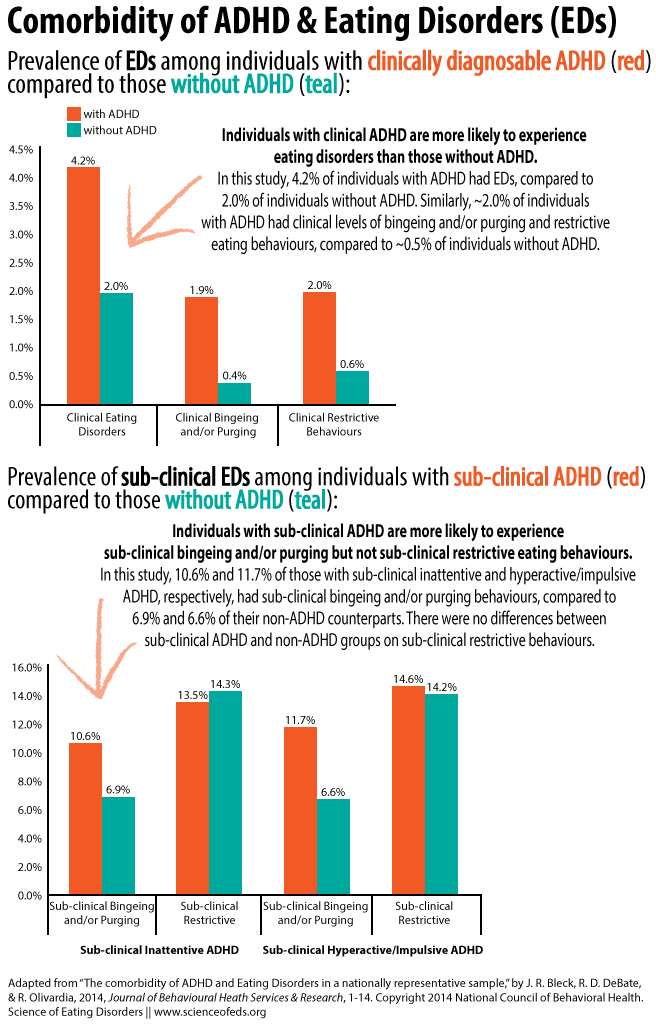

Bleck and colleagues found that 4.2% of those who reported clinical ADHD also reported clinical EDs, compared to 2.0% of those without ADHD. Overall, those with clinically diagnosed ADHD were ~4 times more likely to engage in clinical-level restrictive and bingeing and/or purging behaviours.

Among those who reported ADHD behaviours but were not diagnosed with ADHD, between 10.6-11.7% also reported subthreshold bingeing and/or purging behaviours, compared to ~6-7% among those without ADHD symptoms. Conversely, there were no differences in subthreshold restrictive eating behaviours between those with subthreshold ADHD and those without. There were no differences between inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive ADHD subtypes.

The image below summarizes the main findings:

To summarize,

Findings from the current study suggest that those with clinical ADHD are more likely to experience (a) clinical EDs, (b) clinical-level binge and/or purge eating behaviors, and (c) clinical- level restrictive eating behaviors. On the other hand, those with subclinical ADHD are more likely to experience subclinical binge and/or purge eating behaviors while there was no evidence to suggest a relationship between subclinical ADHD and subclinical restrictive behavior.

WHAT DO THESE FINDINGS MEAN?

Since this was a cross-sectional study, we can’t make any conclusions about the nature of the relationship between ADHD and EDs. Thus far, we just know that there’s an association. There are, however, theories about how the two may be linked:

One theory states that the poor planning and difficulty monitoring one’s behavior manifestations of ADHD may lead to overeating, while another states that ADHD patients may be inattentive to internal signs of hunger and forget to eat when engaging in interesting activities leading to binge eating when less stimulated. An alternative explanation suggests that binge eating is a compensatory mechanism to help control the frustration associated with attention and organizational difficulties.

Not knowing much about ADHD, it is difficult for me to assess how plausible those theories sound. Although, to me, they sound a bit too simplistic. Importantly, the aforementioned theories are not mutually exclusive — it could very well be that all three (or more!) possible causes lead to disordered eating behaviours among individuals with ADHD.

LIMITATIONS

As always, the results must be interpreted with the study’s limitations in mind. Here are the main two:

- All disordered eating behaviours were self-reported and retrospective. Moreover, participants were asked to report on disordered eating behaviours within the previous week only, likely undercounting the amount of individuals engaging in those behaviours.

- An individual was categorized as having clinical-level ADHD if he/she reported being told by a health professional that he/she had ADHD, but the questionnaire did not assess who made the diagnosis and how the diagnosis was made (i.e., was it made using appropriate procedures). (A similar issue is true for the way individuals with clinical-level EDs were categorized as well).

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE FOR CLINICIANS & PARENTS

As findings from this paper suggest, a substantial portion of individuals with clinical-level and subthreshold ADHD exhibit disordered eating behaviours. Consequently, clinicians and parents should be aware of the increased prevalence of clinical and sub-clinical eating disorders among individuals with ADHD, especially bingeing and/or purging, and be particularly vigilant about assessing and/or monitoring children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD for disordered eating behaviours.

For those of you with ADHD and EDs, what do you think of the findings and what do you think may be behind the association between ADHD and EDs? How do you feel your ADHD and ED relate and/or interact, if at all?

References

Bleck, J., DeBate, R., & Olivardia, R. (2014). The Comorbidity of ADHD and Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research DOI: 10.1007/s11414-014-9422-y

I just read this article after seeing the discussion on your tumblr. I recently started seeing a new psychiatrist who diagnosed me with ADHD and put me on Adderall. I have been bulimic for 10 years. I have always been really up front about an inability to focus/ concentrate, but I’ve always been a straight-A student, well-behaved, etc so it seems that I’ve kind of flown under the radar. My peers would pull all nighters and sit in front of their books for hours, and I literally would have to get up every 20 minutes and like walk around the house looking for something to do. I would binge and purge in anticipation of a night of studying simply because I had nothing else to do and “wanted” to waste time because I couldn’t imagine sitting still for that long but would feel guilty if I was doing something fun. I was describing my experience to this new woman, and she told me that sometimes that is why it is detected so late in girls/ women but ADD/ADHD can come in all kinds of forms, and it doesn’t really have anything to do with intelligence. Sometimes, it is about having trouble getting activated with doing the laundry and doing the dishes and keeping your house clean, and I just nodded, and I was like “somebody finally gets me,” and it was so validating after all this time to feel heard and not like “well, you obviously are studying plenty because you test well so don’t worry about it” when I’m like “aaaah I’m losing my minddddd.” I still haven’t told anyone, including my parents, about the diagnosis or the meds, simply because I’m pretty sure they wouldn’t believe me, which is unfortunate because it feels really reflective of my internal experience, which is very chaotic. I still suck at taking my meds properly because when I am at work, I get so busy that I don’t have time to eat, drink, go to the bathroom, etc, let alone take meds. It feels like every day, someone is kicking me off the floor (I work in an ICU) like 3 hours after everyone else has gone to lunch and reminding me to take a lunch break. But I appreciate knowing that I am not alone in this, and I appreciated seeing some of the other articles about adult diagnosis of ADD/ADHD in women with eating disorders.

I (probably) have ADHD (inattentive type) and a restrictive eating disorder. I think they’re related in that the depression, lack of control over my life, and constantly feeling overwhelmed that resulted from my ADHD led to me trying to deal with that by restricting. Also, restriction helps with being understimulated, restless, and bored: it makes everything fuzzier and quiets my mind, sort of a way of self-medicating my ADHD symptoms