What does eating disorder recovery really look like? When you say the word “recovery,” differences of opinion loom large. The lack of definitional clarity around the concept of recovery came up many times at ICED, and continues to surface in discussions among researchers, clinicians, and individuals with eating disorders themselves. We’ve looked at recovery on the blog before (for example, Gina looked at how patients define recovery here; Tetyana surveyed readers about their perspectives on whether or not they thought of themselves as being in recovery and wrote about it here; I wrote about men’s experiences after recovery here). It’s something of a hot topic in the research literature, too.

My Master’s thesis focused primarily on recovery, with one “take home message” being that there can be a disconnect between what recovery means in treatment settings, in popular understanding, and among individuals who have experienced eating disorders. Of course, my study was qualitative and from a critical feminist standpoint, so it is still unclear how well my findings map onto the larger dynamics of recovery. Still, understanding and seeking to define “recovery” continues to fascinate me (good thing I’m doing my PhD on the subject!).

If there is one thing that researchers and clinicians seem to agree on, it is that there is no consensus definition for the concept. And if there is no consensus definition, how can we really compare between studies investigating recovery? With the lack of definitional clarity and the multiple perspectives on recovery that circulate in research, clinical, and “real world” settings, I thought it might be interesting to write a series of posts focusing on how recovery has been conceptualized in the literature. If nothing else, these points of view will highlight how difficult it can be to tie down the construct of “recovery from eating disorders” when the disorders themselves are so complex and require complex solutions.

RECOVERY FROM ANOREXIA NERVOSA USING THE RECOVERY MODEL

To kick off this series, I will report on a very recent article by Dawson, Rhodes, and Touyz (2014) exploring “the recovery model” in the context of anorexia nervosa. What is the recovery model, you might ask? Well, I’m glad you asked.

As Dawson and colleagues explain, the recovery model is based in a movement designed by mental health client (consumer) advocates that can be traced back to the 1930s. Now a part of many mental health programs and services, it is rooted in a sense of frustration with the pessimistic outlook offered to individuals with mental illness prior to this time. You can find out more about the model here and here. It is more than just a perspective on recovery; grounded as it is in consumer advocacy movements, it can also be considered a social movement.

As Dawson et al. note, Anthony (1993; open access) defined recovery as follows:

A deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness. (Anthony, 1993, p. 527, cited in Dawson et al. (2014) p. 3)

Perhaps one of the more surprising elements of this approach to recovery is that it is not necessarily dependent on “going back to where one was before,” in terms of symptoms. Instead, an emphasis is placed on:

- Hope

- Spirituality

- Personal responsibility & control

- Empowerment

- Connection

- Purpose

- Self-identity

- Symptom management

- Overcoming stigma

(From Schrank & Slade, 2007)

This approach highlights facets of recovery beyond remission of symptoms. Patients are also placed in the role of experts over their experiences and are encouraged to seek advice and guidance from others who have experienced similar issues.

Dawson and colleagues sought to determine whether this orientation toward recovery could be helpful in approaches to treatment for anorexia nervosa.

THE PERSPECTIVES OF PATIENTS WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA

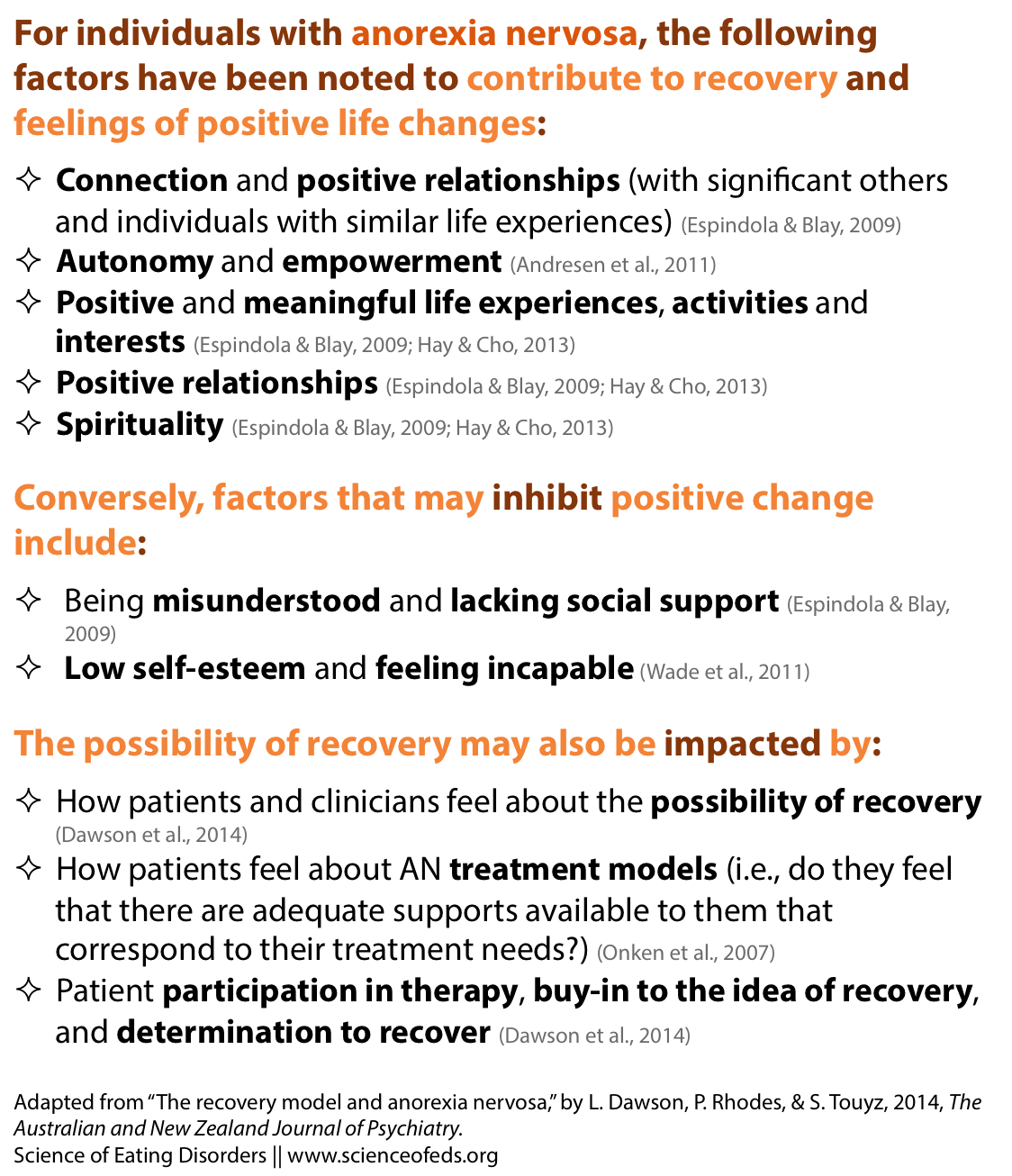

The authors looked to qualitative literature to explore patient perspectives on recovery, reporting on some of the major studies inviting participants to comment on factors they felt contributed to recovery.

None of these findings are particularly surprising; they certainly make intuitive sense. As Dawson and colleagues note, these findings also fit quite cleanly within a recovery model. Again, this makes sense: the recovery model is a very patient-centered approach, and the primarily qualitative literature adding patient voices to the picture indicates that individuals with AN are more likely to recover:

- If they perceive treatment to be effective;

- If they have positive support and experiences in their lives;

- If they feel empowered, and if they think recovery is possible; and

- If they work actively to achieve it

In some ways, the above look like a bit of a “picture perfect” trajectory toward illness; the skeptic in me thinks that it would be rare for all of the above to fall into place at the same time, facilitating an “easy” recovery. Nonetheless, it is possible that explicitly stating these factors might lead to a greater focus on going beyond the individual in work toward recovery, which is something I can definitely get behind. Speaking of treatment and support, how well do the current offerings map onto a recovery model?

TREATMENT MODELS AND THE RECOVERY MODEL

The authors point out that treatment models for AN fit most comfortably with the recovery model in the factors that underlie the various types of treatment, such as the therapeutic relationship, the aims and goals of treatment, and the treatment philosophy.

Evidently, each approach to treatment places emphasis on different pathways to change. Dawson and colleagues offer a few examples of approaches whose philosophies and strategies tend to be more patient-driven and thus more closely aligned with a recovery model (links provide more information, if you’re interested):

- Motivational Interviewing

- Specialist Supportive Clinical Management

- Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA)

- Family-Based Treatment (authors provide Lock et al., 2001 reference)

- Narrative Therapy

In these approaches, therapists tend to place patients (or parents/families) in the expert role, focusing instead on individual or familial impetus and capacity for change. Narrative therapy in particular strikes a chord with the consumer-survivor movement that spurred the development of the recovery model, as narrative therapists have worked with clients to construct “anti-anorexia” and “anti-bulimia” stories that overtly encourage patient resistance (for more on narrative therapy, see this post).

Peer-driven models like multiple family therapy are also noted to be more cleanly aligned with a recovery model, as it tends to bring families together in a mutually supportive environment to facilitate change.

WHY USE THE RECOVERY MODEL IN TREATMENT?

The authors point out that though aspects of the recovery model can be found in many approaches to treatment, it is not consistently or systematically integrated into all approaches to treatment. They go on to offer examples of models of care for severe and enduring anorexia (SE-AN; Touyz et al., 2013 and Williams et al., 2010), which take a slightly different approach to treatment: namely, the focus of treatment shifts from symptom reduction to quality of life improvement. (Tetyana has blogged about approached to treat SE-AN here, mentioning the Williams et al., 2010 study.)

The description of these two programs reminded me of some conversations I have had with Tetyana and others about the possibility of taking a more harm-reduction based approach to enduring eating disorders, rather than continuing to focus on using approaches that (often subtly) equate recovery with being “symptom free.” Going back to the definition of the recovery model, which stipulates that recovery is not simply the absence of symptoms, I can see how these approaches, which shift the focus toward ways to support individuals in achieving their desired quality of life, regardless of their symptoms.

The authors call for further research into the adaptation of the recovery model into treatment, suggesting that this approach may:

- Inform practice by grounding treatment in a “philosophical framework and professional language”

- Offer innovative solutions to long-standing issues in eating disorder treatment protocols (such as redefining treatment goals, engaging with individuals rather than their labels, providing a continuum of care, and expanding focus beyond symptoms)

- Help to bring the patient voice to bear on clinical practice

Given that we continue to search for definitional clarity around the idea of recovery, I think the first point the authors make is particularly timely. If we continue to disagree about and make haphazard use of the word “recovery,” how can we know if we are meeting the needs of the individuals we are talking about as “recovered” (or “not recovered”)?

The last point also makes me very happy: it makes a lot of sense, in my opinion, to honour the voices of the individuals with lived experience when defining recovery and trying to assist in its achievement. If those individuals disagree with the definition you are putting forward, the goals you are setting in getting there, and the ultimate outcome, what is the point?

Of course, I don’t think that the recovery model is the be-all-end-all in defining and supporting recovery, and nor do the authors. They point out that researchers have historically found that individuals with AN may have less desire to change than individuals with other mental illnesses. I’d love to debate this point just a little, but this post is getting a bit epically long, so will leave it at I’m unconvinced about this one as a blanket statement.

Importantly, they note that despite the recovery model’s focus on patient empowerment, the approach recognizes that people may not always make the decision that is best for them, nor do proponents advocate poor mental health care. Further, adopting a recovery model is not incompatible with “evidence-based practice”; in fact, the authors argue that combining a philosophical recovery-model approach with a medical model may be “the best way forward” for eating disorder treatment.

With its focus on patient empowerment and seeing recovery beyond symptom remission, I think the recovery model at least has the potential to open up a discussion around whose voice (or whose voices) are most important in defining and understanding recovery. Of course, it is not the only approach to conceptualizing recovery (more on that in the next post!).

References

Dawson, L., Rhodes, P., & Touyz, S. (2014). The recovery model and anorexia nervosa. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. PMID: 24927735

I have a couple of thoughts on this.

First, obviously what the field decides on with regard to some concrete definition of recovery doesn’t mean that’s what recovery is or should be for others. It will just make it simpler to compare studies. I personally don’t think it really matters THAT much what the operational definition is — it would just be nice to be able to compare studies. It doesn’t mean everyone needs to agree that that’s “for sure” recovery. (And I know you know that, I’m just saying.)

“Patients are also placed in the role of experts over their experiences and are encouraged to seek advice and guidance from others who have experienced similar issues.”

I think this can be problematic when we are dealing with individuals who are young. Are those individuals experts over their illness if they’ve been ill for a very short amount of time? Sure, they know most about their own experiences, but not necessarily about their illness. I think it also causes a dilemma: We know that individuals have the best chance of making a “full” recovery when they haven’t been ill for that long. But usually that’s also when people don’t really want to recover all that much. So then, is it morally and/or ethically justified to “force” recovery/refeeding? And is it even helpful for those individuals to seek guidance from others who are their age? It could be, potentially, damaging to their long-term health. Of course, it may not be, I am just playing a bit of a Devil’s Advocate here. But essentially, when we talk about “patients”, what patients are talking about exactly? Someone who is not all that young and not all that medically compromised?

I mean, if someone who is 14 and has been sick for 6 months talks about symptom management, you and I would probably be a bit skeptical of that, right? But then, if we are pushing some utopian version of a full recovery on someone who has been sick for decades, that’s also just as questionable.

I don’t think we will ever have clarity about recovery. I think we may just have clarity about *our own* recovery.

“The last point also makes me very happy: it makes a lot of sense, in my opinion, to honour the voices of the individuals with lived experience when defining recovery and trying to assist in its achievement. If those individuals disagree with the definition you are putting forward, the goals you are setting in getting there, and the ultimate outcome, what is the point?”

Ah, but this is very, very tricky when in a group setting like inpatient or residential. Can you imagine everyone having their own — *very different* — goals?

“They point out that researchers have historically found that individuals with AN may have less desire to change than individuals with other mental illnesses. I’d love to debate this point just a little, but this post is getting a bit epically long, so will leave it at I’m unconvinced about this one as a blanket statement.”

I am unconvinced as well, actually.

Agreed, I think a definition would be useful for comparability; there is movement to do this from within the researcher-practitioner community for sure. I just don’t really know how broad this definition would need to be in order to actually have any clinical utility though… thinking measurement wise and knowing the issues with self-report measures (but also with researcher administered evaluation, etc…) and then also vast differences in clinical orientations, I feel that it might be really difficult to come up with a definition that everyone agrees on. I think it might be worthwhile, yes, but I think it is certainly an uphill battle that I suppose will involve some pragmatic sacrificing of theoretical orientation to what the construct means for different people (including differences between clinicians, between researchers, and between individuals with eating disorders all from varying social locations).

Well, yes. Adolescents do make everything more difficult 😉 By “experts over their own experiences” I’m using very critical theory/feminist theory language and basically meaning that clinicians aren’t the only ones who know things about eating disorders. With those who are younger, of course they might not have the same insight over what they want out of life in general, let alone out of recovery. But I think what the recovery model suggests is that we need to take into consideration their desires in some significant way. Given that they also cite FBT and multi-family therapy as examples of patient-centered care, I think that the “experts over their own experiences” thing may include social systems/families and not just the patients themselves- the whole empowering the patient and/or their family/friends to be active participants in the therapeutic process toward recovery type thing. Or at least that is my read of how that might apply to ED treatment & recovery.

And yes, the honouring of the voices of individuals/(families/friends too) gets complicated in certain settings, like the ones you mention. I still think that there is more room for working with individuals (and/or families/friends) to determine goals, particularly once the more “obvious” goals have been met- the authors do make a point of saying that the recovery model is not incommensurate with a medical approach to weight stabilization etc.- I get the sense that the recovery model applies more to non-inpatient (or post-inpatient) scenarios.

“I don’t think we will ever have clarity about recovery. I think we may just have clarity about *our own* recovery.”

THIS. I like this. I think that is very, very true (but also even that is hard because of all of the understandings of recovery that get tossed about as the gospel truth that we all hear and can’t avoid…)

Meh, I don’t think it is all that hard to come up with a reasonable definition of recovery, stages of recovery, or different spheres of recovery.

For instance, you can measure several components of recovery: physical, psychological, and social. Physical could be things like weight restoration (if applicable), frequency of behaviours (whichever are applicable), and any symptoms of malnutrition. Psychological could be assessed via the typical assessments (depression, anxiety, eating disorders, body image). Social things could include quality of life assessments and objective things like school/work, etc. So, then we can just pick a battery of assessments and scales and basically we are there. We can divide it up into some definition of partial recovery or different levels of recovery or something.

Of course there are issues with self-report and measurement, but if everyone uses the same thing, then we can compare across studies, assuming that the issues and biases are more or less the same.

I don’t care what people decide recovery is or isn’t. What I want is for any researchers evaluating some treatment or therapy to collect sufficient data so that others can then come and look and make their own decisions. It frustrates me when researchers only assess the physical components of recovery and then call that recovered. I don’t care what you call it, but can I please have some data on the psychological and social well-being of the patients? I’d just want that data to be there.

We don’t even need a definitions everyone agrees on — we just need to decide on some metrics everyone conducting a treatment study is willing to do. Some kind of a bare minimum list so that we can evaluate outcomes. Who cares about the definitions, really.

What are examples of non-patient-centered care?

Is it difficult to come up with a definition of recovery encompassing the spheres you’re talking about? Maybe not. Would it be difficult to get a bunch of researchers and clinicians to agree to categorically use this definition in studies, leading to greater comparability across studies? I would say a resounding YES to that one. I think when researchers and clinicians are coming at treatment from vastly different perspectives, the very use of any instrument designed to measure the construct might be a bit of a sticking point.

I totally and wholeheartedly agree that it is frustrating to see researchers only collecting data on “physical” recovery (i.e. measuring weight and symptom frequency) because I too would really like some more data on psychological and social well being. But, I think that there are multiple researcher/clinician interpretations of “psychological and social wellbeing” that the pessimist in me thinks might impede the application of a standardized definition of recovery across research. I’d be eager to see the definition be as broad as possible, though, if I had my way. Then again, if I had my way I would probably just talk to people all day every day about what their recovery means to them, because that’s what matter to me…

I think the answer to “who cares about the definitions really” is… lots of people, at least anecdotally from my interactions with researchers, clinicians, etc. Then again, maybe I just think people care because it’s interesting to me, too!

I don’t know that the recovery model defines “non-patient-centered care”” so much as it has specific guidelines for what patient-centered care would be (i.e.. care that works to empower and support patients in achieving their goals)- again with the caveat that recovery model does not mean not attending to the medical needs of individuals with mental health concerns. Examples of non patient centred care that I’ve seen tend to harken back to pre-deinstitutionalization movement mental health care (e.g. mental health care in asylums, etc.) From my understanding, non-patient centred care, then, would be any approach that is coercive/forceful in nature; I believe there is some debate about how voluntary the care needs to be though, because of the ethical issues involved in determining when to step up care in instances in which people might not be able to make the best decisions for themselves & acute distress. I should read more about it… I found a few articles doing a quick search that I haven’t yet read & formed an opinion on but that might be interesting for looking at the intricacies of “patient-centeredness” and the recovery model:

http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=1109168

https://www.academia.edu/455869/The_Collaborative_Patient_Person-Centric_Care_Model_CPCCM_Introducing_a_new_paradigm_in_patient_care_involving_an_evidence-informed_approach._Canadian_Healthcare_Network._EPublished_7_March_2011._http_www.canadianhealthcarenetwork.ca_

And there are more like these

Yeah, the ethics of forced treatment are complex and interesting. I wrote an article on it once. There’s no clear-cut solution.

The inability of academics to come together and make some decisions is incredibly frustrating.

Too broad of a definition might lose meaning, as far as evaluating treatments is concerned. The metrics should revolve around the main things that patients and clinicians seek/desire as a result of treatment. Of course, those often differ, so it should be a compromise.

I think people are making it much, much harder than it needs to be. We don’t actually disagree on the big things: recovery includes physical and psychological well-being. Done. Simple. Let’s evaluate it some way.

We are not talking about resolving the Israeli-Palestine Conflict here, you know… this really isn’t all that difficult. The problem is that everyone wants it to be their way.

I think that working with patients one-on-one or patient with a team makes tailoring the approach to suit the needs of the patient much easier. When we get into group settings, then it gets much, much harder.