When it comes to eating disorder treatment, few (if any) approaches are as divisive as Family-Based Treatment, also known as the Maudsley Method (I’ll use the terms interchangeably) . When I first heard about Maudsley, sometime during my mid-teens, I thought it was scaaary. But, as I’ve learned more about it, I began to realize it is not as scary as I originally thought.

As a side-note: I know many people reading this post know more about Maudsley than I ever will, so your feedback will be very much appreciated, especially if I get something wrong. I should also mention that I never did FBT or any kind-of family treatment/therapy as part of my ED recovery. (I have done family therapy, but it was unrelated to my ED; it was a component of a family member’s treatment for an unrelated mental health issue.)

In this post, I want to briefly explain what the Maudsley Method entails and put it into context. I also want to discuss some of the key research studies testing the efficacy of FBT and some limitations of the treatment.

THE MAUDSLEY METHOD/FBT

Briefly, Maudsley is an intensive outpatient treatment approach that puts parents in the center of their child’s treatment. It has three main goals: (1) weight restoration, (b) restoring control of eating to patient, and (3) returning to normal adolescent development. This is achieved in three stages in 15-20 treatment sessions over a 12-month period. (More info here.)

The main difference between Maudsley and traditional treatments is that parents are put in charge of their child’s weight restoration and refeeding. In the first stage of the treatment, all meals are prepared and supervised by a parent and physical activity is minimized. As the patient gains weight, he or she is given more and more control over their food intake. The final stage focuses on adolescent development and typical coming-of-age issues.

PUTTING MAUDSLEY INTO CONTEXT

Nowadays, most clinicians (I hope) understand that eating disorders are caused by a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors. But not so long ago, the blame (much like schizophrenia and autism) was put squarely on the family, namely: the mother.

In the 1800s both Gull’s (in 1874) and Lasegue’s (in 1873) clinical accounts included a list of common physical and behavioral symptoms as well as the notion that families were responsible for the cause of AN and its persistence (Yates, 1989). […] More modern views on etiology emerged in 1960 when Bliss and Branch’s review implicated media messages and social pressures inherent in western societies in the onset of AN (Rehavia- Hanauer, 2003). In the 1970s, psychological and family systems explanations peaked (e.g., Minuchin, Rosman, & Baker, 1978) and in 1973, Bruch described etiology in terms of individuation from one’s mother and the development of personal ineffectiveness (Rehavia-Hanauer, 2003). Accordingly, the notion of enmeshed families and over-controlling parent as causal is nearly archetypal in AN treatment history and still held by many today.

Naturally, when you blame the family for the child’s eating disorder, the most logical solution is to remove the child from the family (perform a “parentectomy”) in order to treat the illness. Naturally, this left a lot of parents out in the cold. They were in the dark about the nature of illness and perhaps more importantly, didn’t know what to do once the child returned home (hello relapse!) Imagine a family member is diagnosed with a mental illness, cancer, or cardiovascular disease, and suddenly you find yourself blamed for causing it, and what’s more, you are completely in the dark about how to manage it. Scary, right?

FBT changed that. It not only lifted the blame from the parents, it sought to empower and utilize them as key figure in eating disorder treatment.

This is why context–context that I wasn’t aware of when I first heard of Maudsley many years ago–matters.

THE EVIDENCE: RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS

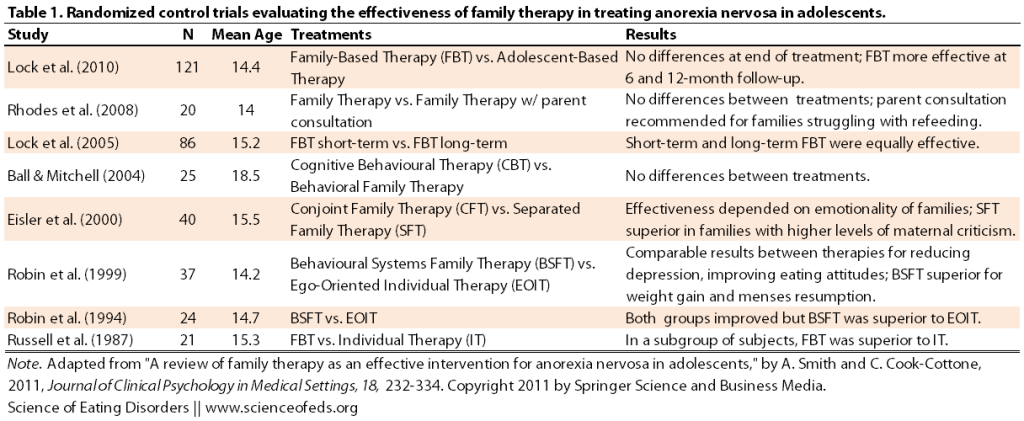

Onto the evidence. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the ‘gold standard’ of clinical trials and are at the heart of evidence-based medicine. In part because the prevalence of AN is low and treatment dropout rates are high, only a few RCTs have been done examining the effects of family therapy in treating adolescents with anorexia nervosa.

I’ve adapted a table from Smith & Cook-Cottone (2011) summarizing RCTs using the Maudsley Method or variations thereof below:

I don’t want to discuss these studies in too much depth, but needless to say, they all have their strengths and weaknesses. For example, the Robin et al (1999) study which showed that a type of family therapy was more effective than individual therapy for weight gain and resumption of menses is confounded by the fact that 58% (versus 28%) of patients in the BFST group received inpatient treatment during the course of the study. So, is it BFST or inpatient treatment that’s responsible for the superior weight gain?

By far the largest and most robust RCT was published by Lock and colleagues in 2010 (freely available online). The study compared standard FBT with individual therapy called AFT (analogous to EIOT). At the end of treatment, full remission was achieved by 42% and 23% of patients in the FBT and AFT groups, respectively. This, however, was not a statistically significant difference (but at p= 0.055, it was almost there). FBT proved to be significantly superior at the 6 and 12-months follow-up periods (49% and 23% at 12-month for FBT and AFT, respectively).

The strengths of the Lock et al study are: (1) comparatively large sample size; (2) collection of data across multiple sites in different cities; (3) using a manualized treatment protocol (which means that, in theory, everyone in one group gets the same treatment); and (4) training and supervision of all treatment therapists.

A criticism, however, is that AFT is not an evidence-based control. From my understanding (and in my experience), most outpatient, inpatient, and residential treatment is multidisciplinary: it includes individual therapy, group therapy, and nutritional therapy, among other things. In this study, AFT was comprised solely of individual therapy (with “collateral contacts” with parents outside of the individual therapy sessions with the patient.)

Edit: Correction to the above from Anon in the comments: “AFT did not consist solely of individual therapy sessions. Both the FBT and AFT groups were seen also by pediatricians with extensive eating disorder expertise who gave guidance on physical requirements for recovery.”

In the end, though, I think Lock et al.’s conclusions are fair and balanced: “The findings of this study together with the existing smaller-scale studies, suggests that FBT is superior to AFT for adolescent AN, though AFT remains an important alternative treatment for families that would prefer a largely individual treatment.”

One important component for why FBT was superior to AFT at follow-up was that patients in the FBT group experienced considerably lower rates of relapse compared to those in the AFT group. This is not surprising: in FBT, parents are integrated into the treatment process and as a result, become much more aware and more educated about eating disorders and what to watch for.

In my opinion, this is one of the biggest strengths of FBT, and it is also why I’m excited about UCAN (Uniting Couples in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa).

LIMITATIONS OF FAMILY-BASED TREATMENT

For an illness that’s soooo difficult to treat, having a treatment approach that works–even for a subset of the patient population–is pretty freaking amazing. And here’s a key point: no treatment for anorexia nervosa will work for the entire population. It is just not going to happen.

From my observation, it seems that some practitioners and/or parents are really into FBT because they’ve seen it work. On the other hand, suffers that had terrible experiences (because when FBT doesn’t work, it can be a disaster) or those who know it would not work for them, get very defensive and interpret the excitement over FBT as an attempt to convince them that FBT should/will work for them and if it didn’t, they must have been doing something wrong.

I see this repeated often and I’m definitely not free of blame. I know I used to (and probably still do) get defensive. This is because when individuals claim that FBT works for 80-90% of adolescent patients, a plethora of different reasons for why that actually can’t be the case in practice flash in my mind. (Please note: I’m not denying results of studies.)

Here’s what I think. We know that FBT works really well for a subpopulation of adolescent AN patients who haven’t been sick for a long time (~12 month on average). And research seems to suggest that for this subpopulation, FBT should probably be the first-line of treatment as it seems superior to other forms of treatment. And given that something works, at least for some patients, it is only logical to see what other ED patient subgroups would benefit from it as well. Adults with AN? Adolescents with BN?

However, I do fear that some proponents of FBT–those that are really into it–sometimes fail to see that it simply cannot be used in many situations. I also feel that some fail to acknowledge the intense self-selection bias to occurs in these studies.

These are NOT the fault of FBT, nor are they criticisms of FBT as a treatment modality. As Laura Collins said on the FEAST FB page recently: FBT is a tool in a toolkit of treatments for eating disorders.

I want to finish by listing just some of the reasons why FBT might not be appropriate. This is not a comprehensive list, and admittedly, it is one that’s formed largely as a result of my own experiences, living in Toronto:

- Language barriers (English as a second language)

- Financial barriers (To pay for it, to take time off)

- Mental health issues of parent(s)

- Mental health or physical health issues of a sibling (or grandparents, for that matter)

- Cultural barriers (to understanding/accepting mental health issues, mental health stigma, etc.)

- Other factors that disrupt family functioning (as an example: unfortunately, homophobic and transphobic parents still exist, and likely in higher numbers among immigrants from more religious or conservative countries)

- Emotional, physical, or sexual abuse

Living in Toronto for the last 15 years, I see families who encounter one or more of these difficulties more often than I see those who don’t.

I think it is irrefutable that FBT works really well for a subset of adolescent AN patients. That’s a great accomplishment for an illness that’s so difficult to treat. But as we continue to search for other treatments for anorexia nervosa, and other eating disorders, let’s be mindful of some of the challenges that some families face (and as I said, in some cities more (a lot more) than others). So, in my view, FBT is mostly hope with a bit of hype (but that probably depends on what circle you are in, too!)

References

Smith, A., & Cook-Cottone, C. (2011). A Review of Family Therapy as an Effective Intervention for Anorexia Nervosa in Adolescents Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18 (4), 323-334 DOI: 10.1007/s10880-011-9262-3

Great article! There are definitely pros and cons to FBT, as there are with any approach. Unfortunately, MOST traditional approaches to ED would be extremely hard to test in a randomized controlled trial, as there are few agreements as to the ultimate goals for therapy (i.e. temporary ‘fattening up’ vs. actually achieving health mental and physical functioning in the long term), the structure and content of the intervention (i.e. most places use some combination of psychodynamics, DBT, CBT, medical monitoring, etc), duration, etc….

Ultimately, I think the answer on ‘what works’ is dependent on the person. And clearly, FBT works for some people. However, I am greatly looking forward to research on the potential harms of FBT (how does it impact those who are NOT good candidates?). As with any medical or nutritional intervention, the research base SHOULD consist of both efficacy information AS WELL AS possible risks, side-effects or any other contraindication.

I do have to say, though, that I have been appalled at some of the comments made by proponents of FBT when the issue of potential family mental health issues is brought up. I have attended conferences where speakers have literally said that we shouldn’t pay attention to that type of thing, or that any dysfunction MUST be caused by the presence of the adolescent’s eating disorder….

But I digress. I like your article and the balanced view it gives.

I agree with you. I think the potential risks can be huge.

I have limited knowledge/interaction with proponents of FBT, except since starting the blog.

I have seen lots of things that did make me roll-my-eyes a lot. It seems that some people are in denial about issues affecting less-than nuclear families. It strikes me, sometimes, as almost privilege-denial. People in certain situations are unable to see or understand others. Particularly when they are blindsighted by a particular thing.

I can understand that it is probably easy to get into that situation, though, as a parent, watching your kid starve yourself to death, and then be removed from any care or wrongly blamed for it. It is reactionary. But, my initial “wtf” reaction to learning about Maudsley was also reactionary due to my own family dynamics and ED experience.

I also think that those of us who spend time on online ED forums are aware of just how many people who are not in treatment/can’t get treatment do not come from families where FBT would ever, ever, be an option. But when you are in a circle of parents who are doing or considering FBT, it is a different perspective.

I suppose I’m a bit sensitive to issues that are more likely to affect immigrants, too.

Firstly, I think it’s great that FBT has been developed and is effective for so many kids. And that whole parent-blaming phenomenon was awful (and is awful, if it’s still happening). But I feel like some of the FBT proponents/parent advocates have reacted so strongly to that (or to any hint of parent blame) that they are overly defensive in the opposite direction. So then you get people claiming that parents have played no part in their child’s ED and that any mental health issues in the parents are merely a product of the ED. I’m sure that’s true for some parents, but not for all. And I’m not just referring to ‘abusive’ or ‘bad’ parents (which everyone seems to agree on). There is a middle ground here. What about parents who are loving and doing their best but DO have their own issues that predate the ED and have had some impact on it?

I know every family is different, but just for example, my mother had OCD, severe anxiety, and was a chronic dieter my whole life (previously having been a compulsive overeater). She was extremely controlling about everything, especially the household food, but she wasn’t in any way abusive; she was never anything but extremely loving and caring and doing her best. That’s just how she dealt with life. Of course there were many other factors (temperament, etc) that led to my AN (and my sister’s BN) and I do not for one second blame my mother! But it is slightly infuriating to be told that my mother’s issues had nothing to do with mine and that my ED caused the problem…And I think there are a lot of families like mine where FBT would probably not have been suitable, not because they are ‘extreme cases’ of toxic parents, but because of the complex issues that were there long before the ED developed and that can’t just be put aside while the family pulls together to administer FBT.

Anyway, sorry, that was really long…I just get irritated because I think BOTH sides can get really extreme sometimes and it doesn’t do anything for their cause. (Disclaimer: I know that just because I and others I know have had certain experiences doesn’t mean this is true for the majority of patients…but the opposite is also true). Okay, rant over! Thanks for the post, by the way! I look forward to the next one 🙂

Oh and PS. This isn’t aimed at anyone in particular, and in fact I really admire the work that parent advocates are doing in the ED world – I think it’s great. My main worry is that extreme views/reactiveness can get in the way of what they’re trying to achieve. But yes enough from me! 🙂

Yes, exactly! I’ve encountered some pretty ridiculous denialism and defensiveness on the part of the parents/FBT proponents. (And also a lot of infantilizing.) Like you said, it is very dangerous when people extrapolate their experiences and/or assume others’ experiences are the same.

We should NOT be dismissive of others’ experiences and their feelings. It is hurtful and gets us nowhere.

Our experience with FBT is with the support of UCSD. To my astonishment, I have seen that families have risen to the occasion when they understand the life of their child is at risk–rather than excluding families with challenges (parental substance abuse, language barriers, single-parent families, UCSD supports them through PHP and equips them to deal with their particular challenges. I think that as we see modified FBT approaches that provide ample support to families we will see more successes using models that put nutrition and weight restoration first.

Fab article, Tetyana. Thank you for this.

A couple of points I would like to raise. Firstly, re Joy’s point about mental health issues amongst other family members (a discussion that has been going on for many moons!).

When a parent is faced with a child starving to death in front of them, the likelihood is that the parent will become extremely stressed, agitated and be in a state of heightened emotion. It is what most parents do when their child is very sick – ask a pediatric oncologist, if you need proof. This does not mean that the parent has caused the patient’s eating disorder because they are highly emotional, stressed, anxious and, in a lot of cases, depressed. This has been a chasm of misunderstanding for many decades (not helped by dear Hilde’s various clinical observations).

Secondly, it is very dangerous to force any patient or parent’s experience of an eating disorder onto other people. Each person has a unique path into an eating disorder and each family is different. I do get so annoyed when patients assume that, because their families were dysfunctional or they have been told in the course of decades of treatment that this was the “cause” of their eating disorder, that this must be the case for the MAJORITY of other patients.

In my wide experience of patients and families (and I would estimate I am well over the 500 families now), I tend to see more and more a correlation between high anxiety and OCD personality types and eating disorders than I do dysfunctional families. Amongst “Older” patients and recovered patients, parent blaming is something that they have explored extensively with clinicians over the past 30 years but the majority of them do not feel it is their parents “fault” in any way and are, indeed, distressed by the “pain” they have caused their parents with their illness (and that, my friends, is a the 7th circle of hell….)

I do see mental health issues amongst parents – depression being the most common and PTS type symptoms, once a patient is on the road to recovery. Nobody apportions blame – any more than my children or my husband blame me for being depressed about the fact that I have cancer…

I wonder if FBT works so well with adolescents because it is a type of EXPR therapy with food? At a stage when there is a tenuous hope that parents just might know what they are on about, rather than being total ignoramuses?

I believe there are trials being run on older patients.

I also think that FBT is a much misunderstood treatment protocol. It is a treatment method, rather than a therapy. It is not CBT, DBT or any such (which are often used in conjunction with FBT) therapy.

Delighted to answer any more questions but would like to add the caveat: we botched together a form of FBT from the L&L book because we had no access to that type of treatment. Indeed, our standard NHS treatment package consists of 6 CBT sessions. That’s it. Total treatment package for anorexia nervosa in a 12 year old….

I am not therefore able to give first hand experience of FBT – few people in the world have access to it (and they mostly live in Chicago or SD!)but I am happy to defend it as a treatment protocol!

I feel every time I bring up things like mental illness and other factors standing in the way of FBT, people assume things like depression or anxiety. That’s fine. I get that. But mental health issues in my family were much more severe than that, and predated my birth by years.

Otherwise, I do agree with you that it is important not to discount FBT just because there might be ED-related issues in the parents, because obviously, for most parents, seeing your kid starve and refuse to eat is bound to lead to heightened anxiety.

I never had the experience of working with clinicians who blamed my parents; and I never blamed them either. One of them was certainly really UNhelpful in recovery, but they weren’t to blame for it, I just knew that real recovery would have to wait until I moved out. But, I realize my circumstances are, thankfully, not the norm. But man, they are not that rare.

Here’s the thing I tried to point out. The families like my own, or more dysfunctional, or perhaps even a bit less dysfunctional, are the kinds of families that you are much less likely to interact with. That’s not a bad or good thing, but it does shape your perception of family dynamics that are common in ED patients.

There’s so much self-selection bias when it comes to these issues, that I often feel people in my circumstances, or similar, get discounted in FBT circles (from what I’ve seen, anyway) because they themselves haven’t come across the level of dysfunction that existed in my family. Well, yeah! Naturally..

I’m happy no one ever blamed my parents, though. No one ever really tried to find the “cause.” It was about treatment and reducing day-to-day triggers (like stress, or anxiety) which eventually led to symptoms.

But but but

Nowadays, most clinicians (I hope) understand that eating disorders are caused by a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors. But not so long ago, the blame (much like schizophrenia and autism) was put squarely on the family, namely: the mother.

I wish, Tetyana. I really wish that most clinicians did understand and did not blame the parents. Sadly, experience tells me otherwise.

There are a lot of younger clinicians coming through who are more up to date with the more modern ideas on the etiology of an but, sadly, those clinicians who trained in the 70’s and 80’s and 90’s are now nearing the top tier of the profession. In my experience (and that of many other parents), they still cling firmly to Hilde and others who espouse the toxic family theories. In ed world, we are waiting for dead men’s shoes – as those at the top of the profession retire, there is a chance that younger, more “educated” clinicians will filter through and the terrible misunderstandings that are presently destroying lives will retire too. It happened in the world of autism but took a long long time. In the meantime, people are dying because of lack of good treatment and stigma. And that makes me cross.

I spend a lot of time defending parents, good parents, kind loving parents. That does not mean I think that ALL parents are good. There are some horrible and toxic parents out there. However, for too long, ALL parents have been tarred with the same brush.

This does not mean I discount your experience or the experience of other patients whose nurture has contributed in a large part to the onset of an eating disorder. I am trying to defend those parents (who I believe are in the majority) who are doing their best to cope with a terrifying situation and are shouldering unjustified guilt and blame from clinicians at the same time.

We do have parents who have had eating disorders in the past. We are unable to deal with parents who have an active eating disorder and Julie O Toole has covered this in her blog post.

However, I would never discount you or your circumstances. Nor would I recommend that your family tried FBT. It is a treatment protocol that is not going to work for a highly dysfunctional family, me thinks.

Of course my perception is different from yours. However, if you ever fancy being adopted by a mad English farmer, just let me know!

Oh, I agree with you. I understand what you are defending and why, which is why I emphasized putting FBT/Maudsley into context. I think that is really important. I do think families like mine are the minority, overall, which is good. And perhaps being in Toronto, my experiences with clinicians are also quite different from many others. Like I said, I don’t think everyone or even most people discount others’ experiences.

But I think the mix of people in my situation (or people for whom FBT didn’t work) and those for whom it did/feel they have been blamed for their kid’s ED creates a situation where there are two camps both being defensive and reactionary. (And I can understand why.)

I just wanted to emphasize, like you said, that we should be aware of our own biases based on our experiences and the biases that are inherent in the RCTs. It doesn’t mean our experiences aren’t valid; they are, of course. It just means we shouldn’t be so quick to tell others how to feel, think, and what should and shouldn’t work for them.

Stunning…well-written, reflective article and excellent analysis of research.

So hoping for the day when a variant of this type of treatment becomes available to an adult anorexic population. Relapse post-hospitalisation is so very real and anxiety-provoking when one is in charge of all things “food” in the household…and it is too easy to fall into former, self-restricting patterns in a lame quest for an inner “control”..which, of course, means LACK OF. Sigh..but thank you .

I have a hard time imagining what an adult variant of FBT would be like–the power dynamics are totally different, a spouse doesn’t have the kind of authority over their partner the way parents do over children. Of course, spouses do provide care for some chronic illnesses (e.g. cancer) but not to unwilling patients. I can’t help but think that could disturb the relationship dynamic in ways that could be quite ugly and abusive.

Does anyone have anecdotal evidence of how this could work in a healthy, successful way?

Bulik and colleagues at UNC-Chapel Hill have a program called UCAN (Uniting Couples Against Anorexia Nervosa). It involves significant others but doesn’t charge spouse/partner with making nutritional decisions.

The University of Chicago published a case series on FBT for young adults (I believe through age 24) with AN which is much more similar to FBT for adolescents.

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10879-010-9146-0

I’ve blogged about UCAN before (the link is in the main post).

I’ll check out the UofC FBT study, thanks for the link!

Very small, just 4 patients, but it’s an interesting paper.

I didn’t do FBT, but my partner’s involvement was really helpful in my recovery. I think one key thing is that adults, particularly if they are in an important relationship that’s clearly being hurt by the ED, are much more willing to accept or ask for help. Young kids early on in the ED might be in denial, but when you have had an ED for a long time, and you are in a relationship that you have chosen to be in (vs. parents, who we don’t get to choose), I think it changes things. But I do agree it can get ugly, of course.

AFT did not consist solely of individual therapy sessions. Both the FBT and AFT groups were seen also by pediatricians with extensive eating disorder expertise who gave guidance on physical requirements for recovery.

Thanks! I somehow missed that. I’ll add that info to the post.

Just my two cents, but I think it really might be a significant factor. “Supportive clinical management” does as least as well as two types of psychotherapy for adult AN. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21997429

The medical care kids with AN get from community pediatrician isn’t always all that great. My guess is specialized pediatric care was a big advantage to both groups in the Chicago/Stanford study.

Thanks for the link to the study. And yes, I would agree with you.

@ Donna

A Case Series of Family-Based Therapy for Weight Restoration in Young Adults with Anorexia Nervosa.

Chen EY, Le Grange D, Doyle AC, Zaitsoff S, Doyle P, Roehrig JP, Washington B.

Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. April 2010

Abstract: This case series aims to examine the preliminary efficacy, acceptability and feasibility of Family-Based Treatment to promote weight restoration in young adults with anorexia nervosa. Four young adults with sub/threshold anorexia nervosa were provided 11–20 sessions of Family-Based Treatment for young adults with pre-, post- and follow-up assessments. At post- and follow-up, 3/4 participants were in the normal weight range, 3/4 were in the non-clinical range on the Eating Disorders Examination and reported being not/mildly depressed. At post-treatment, 2/4 were in the good psychosocial functioning range and by follow-up, 3/4 were in this range. These results suggest that Family-Based Treatment for young adults with anorexia nervosa is a promising treatment.

Thanks again.

For me there was no debate. Feeding a child is natural. Getting tools to do that when a child was starving herself was helpful. Doing it at home instead of a hospital made sense. The traditional advice “don’t be the food police” sounded idiotic to me. I am her mother. It is my job to feed her. That’s what I did when she was a baby and toddler and couldn’t feed herself. Yes, now she is 7-8 years old, and *should* be able to feed herself, but clearly she can’t–she is starving. So how do I feed this child?

Also, there are many parents doing modified versions of FBT. Modifications include moving much more slowly through the stages with kids who have pre-morbid conditions (like my daughter). We are nearly one year from diagnosis. She’s been WR for nine months, with weight going up and up as she grows. And, her eating is all still supervised. She appreciates that because it keeps ED, whom she sees as a monster, from taking back any control. In many ways she is eating like an 8 year old–she can have seconds, and I give her smaller portions these days so she can do that. And her weight is still great.

Unless there truly are parenting or family problems, or abuse, or it really isn’t working for unsolvable reasons, family-based care is common sense. However, much much more support is needed–household help, in-home caregivers, etc., to make it work. It is a HUGE financial (leaves of absence from jobs, hiring of help, etc.) and emotional drain on families. But, hey, my daughter is healthy. I prevented her body from being damaged by starvation. It’s been great to see her come back to us, to see her brain/mind improve, to see great results from CBT and exposure therapy, etc. And, I’m very grateful to all of the experience parents from the Around the Dinner Table forum who are not FBT zealots, but are committed to family-based care for their suffering members.

(And, remember FBT is not the only model of family-based care–also read “Give Food a Chance” which recommends a much longer period of structured, supervised eating.)

Anne, thank you for your comment and your feedback.

I think one problem I have is that adolescence is from 12-18, but an 18 year old is very different from a 12 year old, and way more grown-up than an 8 year old. Which is to say that I think when it comes to, say, patients under 14/15, there are probably more benefits to FBT than to inpatient treatment (again, assuming parents are able, etc, etc.) But after that–as power dynamics change, and kids mature, I am not so convinced.

We recognize the problems of doing FBT with adults, but what I’m saying is that I think we need to stratify even more.

With all due respect, I don’t buy the argument that it is the job of the parents to feed their child, so FBT is logical/make sense/natural/intuitive.

I’ll explain. I work as a private tutor. When it comes to tutoring kids in high-school, parents often tell me that they know the material and they can easily teach their kids, in theory, but the problem is that they get into arguments, fight, the kid cries, the parents get really frustrated, and even angry. It is a disaster. So they hire me. Why? Because I essentially get paid to be patient, and to be an outsider. I’m not emotionally involved–this is not my kid. My job is to patients and thoroughly explain the material. It is much easier for me not to get into an argument, and because I’m an outsider, I get automatic respect/authority.

I think that applies to ED treatment in a very similar way. Clinicians are outsiders. It is their job, their expertise, to treat this disorder. Does it mean they are always good? No. Some tutors are crap and sometimes I’m not good at teaching, either. But there are clear benefits to it, as well. Particularly in kids ages 13/14-16/17, or so, during that messy developmental stage. But they are paid to be detached.

From what I’ve seen, when FBT fails, it is for these reasons. Parents get frustrated, angry, and even abusive. The dynamic between a parent-child relationship is very different from a child-clinician relationship. At some ages, it might not matter as much, but as they get older, I think it becomes more important to be mindful of it.

As someone whose family used FBT in my recovery from anorexia I have experienced both the strengths and weaknesses of the Maudsley method. I was sick for just over two years and it took almost another year and ½ for me to regain all the weight I had lost and have cognitive effects (lack of concentration etc.) dissipate. I realize that I am very lucky that I am physically recovered although I feel that my mental recovery has lagged somewhat.

FBT was challenging from the beginning because of conflict in in my family (that had pre-dated my diagnosis) and my parents never fully worked together as a team. This was challenging because I ended up feeling like I was doing 90% of the work of feeding myself etc. even when part of FBT seems to be enlisting family support of the sufferer.

My recovery was not fully supported by my parents and there were many times where I was left at a table alone with a plate of food (a parent was supposed to eat with me) and did not have adequate therapy or support to eat enough. I think this may be why it took me a relatively long time to gain weight.

As I move forward I feel that I don’t know how to prevent myself relapsing when I am living on my own (because not having a parent watching you closely changes things). Even though I am at a weight appropriate for me as deemed by a doctor, therapist and my parents I feel that there is a chance that I will relapse and that I need the tools to prepare for that, just as my parents needed to tools to be able to “re-feed” me. The strength of FBT is that I have been able to test the waters and go away from home for a couple of weeks or months before truly living on my own. There are parts of FBT that are valuable and intuitive to the way we should care for someone when they are sick such as: creating a support system for them, putting on weight before therapy, not blaming parents. Gwyneth Olwyn is a proponent of the Minnie-maud guidelines which utilize some of these strengths.

However, I think that FBT is lacking partly because there are very few good therapies or treatments that a sufferer can turn to after they regain weight. This is precisely why we need to focus on other treatment modalities in conjunction with FBT. Additionally many families end up employing modified FBT instead of strict FBT and this is often overlooked by critics; I was lucky that my treatment provider was able to adapt FBT to my family situation. FBT was absolutely terrifying for me (and I know it was hard for my parents). I think that many people think that FBT could not be effective in any other relationship but parent/child because the person who is insisting upon the sufferer eating must have some sort of power.

However, I think people misjudge the power of a friend or a spouse as a support person. Eating disorders isolate us, and in order for us to combat them maybe we need to work against that tendency by empowering our loved ones to help us rather than keep them out of the loop. Of course some families are dysfunctional but most people have at least some positive relationships in their lives. I hope that people seriously consider using FBT but also that clinicians and researchers (and parents) understand that it needs work and that there needs to be further research and development in other treatments for ED patients of all ages.

Thank you for your insightful comment Anon! I think what you said is incredibly balanced and I agree with pretty much everything you wrote.

I think that we should emphasize empowering someone who the individual may trust or may be the most appropriate caregiver; that’s not necessary parents.

The only thing I’m confused about is: “The strength of FBT is that I have been able to test the waters and go away from home for a couple of weeks or months before truly living on my own.”

I’m not sure how that has anything to do with FBT?

Best of luck with recovery, Anon.

Again, I appreciate the comment.

Cheers,

Tetyana

Thanks for your reply! For me it has been helpful to have my parents involved when I leave home for short periods of time on a class trip etc. I know that when I come back (if anything has gotten out of balance) I have a FBT based system to get back on track. This has been instrumental as I transition to living on my own because my parents have not allowed my weight to fall too far, and I have been able to progress in my recovery while being socially active (which in turn has helped with my recovery). At the same time I feel that I need to have the tools to recover from a “slip” on my own (the other part of my previous post).

Right, I get that. I feel this way with my boyfriend, but we are obviously not doing FBT or anything. Structure just helps a LOT, especially if you don’t get TOO structured and obsessed with it, I know it can develop into a problem, but for me it is great.

It helps to have a loose schedule or some idea of meals, etc..

My response is very late, but thank you for addressing Maudsley comprehensively – the evidence behind it, its usefulness, and its practical limitations (few people touch on this). For families whose circumstances permit it, FBT is revolutionary, so it’s no wonder why the treatment’s biggest proponents include many of these families. But it’s not appropriate for all eating-disordered people and their families. Thankfully, my therapist during the ED recognized my father’s abusiveness and didn’t recommend FBT. If she had, I’m positive that FBT would have become another arena or avenue of abuse.

The other scenarios you named (I hadn’t considered them in the context of FBT before!) … I’m wondering how the stereotype of AN (especially)/BN/purging disorder as psychiatric conditions of privilege and naïveté (white privilege and class privilege, youth and femininity) leads some providers to overlook cross-cultural and cross-class issues in treatment.